Student’s Grandfather Fought for Equality

Rainbow Beach was a popular local beach on the Southside of Chicago off of Lake Michigan. However, it was also heavily segregated in the 1960s, and if any person of any minority were to try to enjoy the beach, the racial slurs and taunts would be louder than the beach waves. Any authority there would turn a blind eye. Sometimes individual African-Americans would swim despite the angry white people, but the most significant protests to the racial divisions on the beach were the Rainbow Beach Wade-ins.

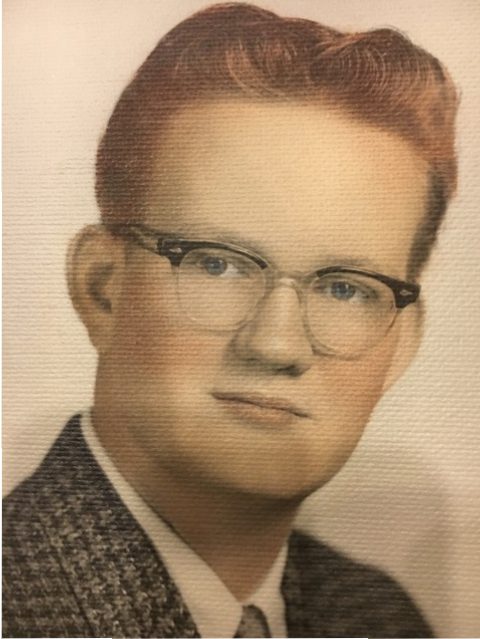

On a remarkably cool August morning, Tim Buckley protested the legally supported segregation of a public beach. Mr. Buckley, my grandfather, was only 18 years old and part of a small, interracial group protesting the segregation of Rainbow Beach. Those watching were hostile and angry, throwing stones at them and calling the protestors racial slurs. One protester suffered a head injury from a rock that gave her 17 stitches.

“At the time,” Mr. Buckley said, “we lived in a very segregated society, and the basic feeling was, the whites wanted to protect their segregated society, and didn’t want to have interactions with the blacks. So they felt this Rainbow Beach was their sacred place. It was kind of ‘Don’t step on this territory, this is an all-white territory,’ and they wanted to maintain a segregated society.”

Even though Mr. Buckley is a white man, he had seen racial discrimination during his time working in the inner city of Chicago at an Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO), which was one of the programs created by President Lyndon Johnson to fight the War On Poverty. As a child he moved around a lot but always lived in all-white neighborhoods because of the color of his skin. It wasn’t until he moved to Chicago’s poorer neighborhoods that he saw the harsh racial discrimination.

“I don’t think I really knew there were such differences in our society,” Mr. Buckley said. “I mean, when you grow up in a setting, you expect everybody has a life like that. Until you go and live in an inner city and realize it ain’t that way. Poverty is very insidious, and part of poverty is because of racism. So I would say I was a naive white guy. I don’t think people were sensitive to injustice, and they didn’t think it existed. It wasn’t an area of interest, not until the Freedom Riders started riding into the South did we start testing it. It was kind of an accepted way that things were. Whites went with whites and blacks went with blacks.”

Around that same time three years later, Mr. Buckley traveled to Washington DC to join the March on Washington with thousands of others. It was there, that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Mr. Buckley was standing at the National Mall when he heard it.

“I think the basic feeling that I would have as a result of the March on Washington was a sense of solidarity and a feeling that we were on the right side,” Mr. Buckley said. “King’s speech was inspirational. Hundreds of thousands of people came together as one. We were not violent, which was the fear — that there was going to be a violent amount of people in Washington — but we were nonviolent and we were united.”

After the march, protesters from Chicago traveled back to their city by a special train just for the protesters. The ride back was overnight, so they slept in their coaches. They woke up the next morning in Indiana, stopped at a station, and picked up that morning’s copy of the Chicago Sun-Times. The March on Washington was on the front page. But along with that, there was an editorial that seemed to be criticizing the march and its importance. According to the United Press International, the editorial stated that “the time has come for the demands of Negroes to be taken out of the streets and into the conference rooms, as is happening in Chicago on school board complaints and job placements.” To the protesters, the article minimized the importance of the March on Washington. They got off the train and assembled in the center of the station. The protesters had become a mob and decided to march on the Chicago Sun-Times.

“We had this very emotional, strong march [in Washington],” Mr. Buckley said. “We were all really pumped up and felt really good about what we did. So you could feel the tension build in the train [about the editorial], and as the train was pulling into Chicago everybody was saying, ‘We’re gonna march on the [Chicago]Sun-Times!’ Interestingly enough, a woman in the back of the crowd started singing “We Shall Overcome” and then the entire group started singing. There’s something about that song that just relieves tension, and then you realized, we weren’t going to gain anything marching on ‘the [Chicago] Sun-Times,’ and so we dispersed and went home.”

A group of about 200 to 300 people actually did go and march on the Chicago Sun-Times that same day, and a few even met with the newspaper’s editors. The next day the Chicago Sun-Times released an apology.

In 1965, the footage of peaceful protesters who were marching across a bridge in Selma getting brutally attacked was released. After seeing the footage, Mr. Buckley flew down to Selma to join the protests. He arrived on Sunday, March 14, but was confined to the area around the Brown Chapel until Wednesday, March 16, when they were allowed to march. While waiting for clearance to march, the protesters would maintain a protesting line in shifts. When Mr. Buckley wasn’t protesting, he had time to himself to do what he wanted. One day he was walking around the city with an interracial group of fellow protesters. They were crossing the street when a car full of white teenagers sped up as if they were going to hit the protestors. Luckily Mr. Buckley and his friends ran across the street, but the white teenagers enjoyed scaring them. It was similar to another incident Mr. Buckley experienced about five years later when he was back in Chicago. As he was crossing the street on the way home, he was almost run over by a car full of black teenagers, who had a lot of fun scaring him, a white man.

“What was interesting was that I realized right there that it’s an example of racism,” Mr. Buckley said. “And what I’m saying here is that these anonymous black youth ran their car at me because I was white. They knew nothing about me. And in the south, this anonymous white group ran their car at me because I was with black people. What I’m saying is that you don’t really know the person, you’re judging a person by the color of their skin and that is a graphic example of an experience where personally, I felt racism — judging people because of the color of their skin — from both sides.”

When the city of Selma finally let the protesters march on Wednesday, about 50 people marched to the Mayor of Selma’s house, including Mr. Buckley. According to the book, Selma, 1965, the demonstration grew “crazy and dangerous,“ so the protesters were taken by a school bus and placed under protective custody by the police of the city of Selma. The city police chief, Wilson Baker, was someone trying to be a peacemaker between the levels of law enforcement in Selma, which included the state troopers, county sheriffs, and the city police. Mr. Buckley and the others spent the night sleeping on the courtroom benches, fed grits and fatbacks for breakfast, and were released in the morning. They rested back at the Brown Chapel until Sunday, March 21, when they began the march to Montgomery. All the protesters marched the first seven miles, but after that only a set number of people could continue; the rest had to return to Selma. That was the last march Mr. Buckley would participate in, and although those three marches were all fighting for the same cause, there were definite differences between them.

“The Rainbow Beach one was very hostile because that was one where people were very angry that we were doing that,” Mr. Buckley said. “The March on Washington, I would describe more as a rally. We were all going down there. There was no tension, conflict type stuff. In fact, the City of Washington was in fear that the whole city was gonna break out in riots because of all these activists that were coming in. And the Selma one was hostile, and scary, and there were some threats. I would say that Selma and the Rainbow Beach one were fairly similar.”

This Saturday, Jan. 21, Mr. Buckley will be protesting in downtown Austin in coordination with the Women’s March on Washington held that same day for women’s rights in Washington DC. At the age of 74, Mr. Buckley may not protest as much as he used to, but still remains aware of today’s issues that need to be dealt with.

“I think if I was 23 today, I would probably involved in Black Lives Matter and the movement about the 1% having everything. I probably would’ve been a stronger Bernie Sanders supporter, and I probably would’ve ‘felt the Bern,’” Mr. Buckley said. “I think [racism is] still in our society. This whole issue over voting is a concern. What do I think the next step would be? I think the next step would be hope in the next generation; folks like you will not treat or judge people by the color of their skin, but — as Martin Luther King Jr. said — ‘by the content of their character.’”

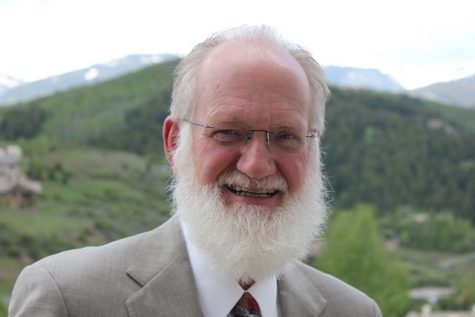

Mr. Buckley in Colorado for his daughter’s wedding

Besides sleeping and doing homework -- which I do a lot of -- I enjoy eating out with my friends and going bowling. When I’m out with my friends, I enjoy...