Romero’s ‘Dead Trilogy’ and The Politics of Zombies (Part 1)

Noire Histoir

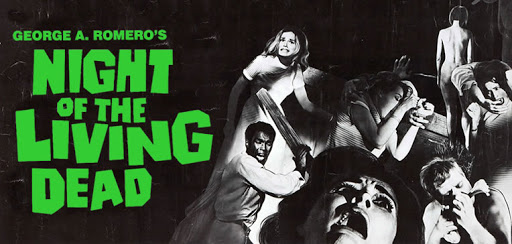

The poster for ‘Night of the Living Dead’, showcasing all the lead characters and a few zombies. Image Courtesy of Noire Histoir.

Introduction of the Dead

While cooped up in my house, with endless entertainment at my fingertips, I was instantly reminded of George Romero’s Dead Trilogy. These three films, made between 1968 and 1985, were unconnected in terms of plot, but in terms of themes, they shared many elements. The heroes fought against zombies by holing up in a single location, often turning on each other and causing their own downfall. Another element shared between these films was they all featured Black protagonists, a rarity in the time in which they were made. As is often the case in horror, the Black guy always dies first, but not in these films. They are not the sassy comic relief, but are instead simply human like their fellow apocalypse survivors, and are often more capable than their white counterparts.

But perhaps the most interesting part of these films is their social commentary. Because all three films came out in different decades, they each have their own commentary on their decade’s social problems. During quarantine, these stories of outsiders being locked in a single locati

on and slowly going crazy obviously hits close to home. Decade by decade, they revolutionized the horror movie form, each being completely different from one another, both in terms of tone and visuals.

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

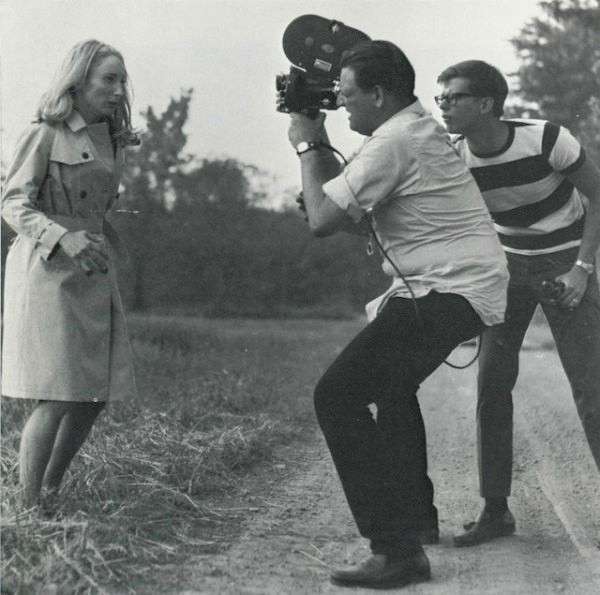

We begin in the 1960’s. George Romero was an industrial filmmaker in Pittsburgh, directing commercials and training videos with his friends Russel Streiner and John Russo. But he and his friends were bored with making these dry films, and they yearned to make a real mark on the film world. They initially wanted to make an arthouse film, something experimental and edgy. But they figured it would be more financially viable to make a horror film, seeing as how schlocky B-movies like the kind produced by Roger Corman were hugely popular among children at the time. But Romero and his friends didn’t want to produce schlock. They decided to mix their arthouse aspirations with the low budget horror and sci-fi that was in vogue at the time. With these two disparate influences combined it created the most influential horror film of the ‘60s.

The first masterstroke was the casting of Duane Jones, a Black actor, as the main character. While this is nothing unusual now, in 1968 it was extremely unusual to feature a Black actor as the lead. And on top of that, the character Jones played was not a caricature or negative stereotype. He was not a sassy sidekick, nor a lazy servant. He is the most capable character in the film, and frequently comes to blows with the old white man, who wants them to hide in the basement. If one looks at this with an analytical eye, his aversion to change can be interpreted as a comment on the older generation’s hatred of change and other races. All the actors were local community thespians, and this lends the film a realistic feeling. These are not the polished faces of movie stars. They are real people.

That said, the movie is not without flaw. This is to be expected, of course, as most films from this time have been dated by their special effects, visuals or acting. Notably Judith O’Dea’s acting as the extremely flaky Barbara has not held up well, as most of her performance is made up of screaming and flailing in fear. The music was not original, being culled from non-specific “library music”, themes made for any purpose to be used in films or TV. If a production company could not afford a film composer, they would use these themes for a small fee and cut it into the film. This sometimes leads to music that doesn’t really fit to the picture. In many scenes, the music sounds very redolent of the cheap horror films of the time, all tuneless brass and plodding rhythms. However, in many other scenes, the music comes off as avant-garde and astonishingly modern.

These experimental themes are used mostly towards the end, playing in the film’s most shocking scenes.

First was the little girl’s murder of her mother, a gory scene that still shocks today. It was bloodshed unlike anything anyone had ever seen, and at the hands of a child no less. Many interpret this as a comment on the younger generation turning on the old, but regardless of intention it’s still a shocking scene.

But Romero saves his real views and his most biting commentary for the final scene. Everyone has been killed or zombified except Ben, the strong Black man. He has been the sole voice of reason throughout the film. As the sun rises, the police and a rag tag group of militia stroll up to the house that Ben has been hiding in. He looks out the window towards the oncoming group of redneck police, but they aren’t in the mood to help. They shoot him, and he falls, lifeless, onto the ground. Whether or not he was killed because they thought he was a zombie or they were racist is not made clear. Perhaps it was a mix of both. They grab his body on meat hooks and then throw his body into a bonfire. These images, captured through photographs instead of film, evoke the black and white pictures of KKK burnings and police brutality that saturated the media at the time. And as we are still seeing these things today, these images still shock and terrify.

Even more shocking is that the film, by far one of the most influential horror films ever made, cost only $114,000. By comparison, 1986’s trash classic Chopping Mall cost $800,000 and it looks and sounds worse than Night. The heir to Night could be seen as the original Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Both were filmed by amateurs with barely any experience, star entirely unknown local actors, kickstarted new genres (zombies and slasher films) and were recorded in small fringe communities (Pittsburgh and Texas). Both hold up today and are legitimately terrifying to watch.

Night essentially single-handedly created zombies as we know them today. Before 1968, zombies were based around voodoo, and were frequently portrayed as African people, giving them an undercurrent of racism. Romero never refers to the creatures in his film as zombies, and knowingly subverted their traditional roles as mindless slaves of white “masters”.

The film was a huge success upon release, but Romero and his cohorts didn’t receive as much money as they could have from distribution: After the original title was changed hastily to the current Living Dead one, the title writers forgot to put the copyright on the title card, therefore s

ending the film into the public domain. What this means is that anyone can re-release the film, re-edit it, post it on YouTube, or make copies of it without litigation from the filmmakers or having to pay a fine. This has made the film widely available, and has only cemented its status as a classic due to it being so easy to find. Unfortunately, this also means that it’s more difficult for Romero to earn royalties from the film, which put him in an awkward financial position when it came to the follow up.

Although it was hugely successful, Night was hated by critics. Despite its genius, the film did not play well for the horror-hating film critics. Now, of course, the film has become a critical darling, and is rated as the sixteenth best horror film on Rotten Tomatoes. In my opinion, Night is the most influential horror film ever made. Before its release, horror movies were frowned upon and were not at all scary. They were low-budget schlock like The Brain That Wouldn’t Die. Night proved that this genre could be just as viable as dramas, and could also be legitimately terrifying on top of that, even on a low budget. Since its release, low-budget releases have proven to be just as successful as the latest Conjuring. Night paved the way for future low-budget horror classics like Halloween, Blair Witch Project and Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

For the remainder of the ‘60s and most of the ‘70s, Romero made small low-budget films that, while beloved by cult audiences, never received the huge attention that Living Dead got. Romero made a film with much of the same tone as Living Dead with The Crazies in 1973, but it would take until 1978 for him to make his masterpiece, perhaps the most iconic zombie film of all time… Dawn of the Dead.

Class of 2023

I am currently Westwood Horizon's video editor, and also one of the hosts of Friendcast, our website's podcast video series. In addition...