Class of 2023

Ardent advocate of em dashes, pastel cardigans, and above all, the written word. Amoli and I are honored to lead a publication by students,...

RRISD Community Amplifies Discussion on Intersectional Solutions to Gun Violence

June 20, 2022

Humanity pulsates in a rhythm akin to the sounds of discomfort, resilience, and loss. For a nation in reckoning, processing the familiarity that lingers in recovery following gun violence tragedy is personal.

Again we are reminded that there is no one story.

No one perspective.

And certainly, no one solution.

The aftermath of events at Robb Elementary School rebound. A grief tinged by the darkness of crises aggravated through pandemic times has shattered silence on challenges faced in education and its relations with law enforcement and gun control.

Where school districts alike have joined the residents of Uvalde, Texas in mourning, many have responded with their own intentions to harden security. As RRISD remains largely uncertain in developing plans to respond, students, staff, and parents alike are not alone in their worries.

Since 2021, local grassroots advocacy group Access Education RRISD has hosted community-wide engagement opportunities bringing key issues to the attention of district leadership.

“No single action we can recommend to our school board will keep kids in Round Rock ISD safe from gun violence when American culture is steeped in violence and inequity,” Access RRISD said in a statement on the Uvalde shooting. “Many steps must be taken, by many people, at many levels, in order for this awful trend to shift. This problem is so much larger than making sure the back door is locked or another SRO or counselor is hired.”

Craig Beers, a member of Access RRISD, is a parent of an incoming sixth grader and third grader. His decision to increase his involvement within school board processes, like many, came as a result of the structural changes to learning caused by the pandemic. This choice also coincided with a desire to understand the decision-making that would factor greatly into his children’s transition from elementary to secondary education. Sharing worries over the sheer frequency of gun violence in schools coupled with the stagnation of progress, Beers emphasizes the grim reality hindering comprehensive policy change.

“Statistically speaking, it’s something that is still relatively rare,” Beers said. “That’s not to say that fear isn’t always there. This is something that could be prevented. There needs to be gun control. That’s the single most [prominent] issue here of why this is occurring; locking down more schools [and] God forbid, arming teachers is just wild. It doesn’t happen anywhere else in the world.”

In light of recent incidents, Beers facilitates such conversations with his own children. Pointing to the importance of identifying preventative measures, Beers looks at the continuity of past events as a telling avenue to strengthen discourse on the complexities of firearm safety.

“I try to teach them about what happens if they encounter a gun [and] what gun ownership in Texas [looks like],” Beers said. “If they visit somebody’s house, there’s probably a high likelihood that person may own guns, and they may have guns just laying around. The schools already teach ways to avoid conflict, so [I reiterate] those points at home.”

With increased investment in campus safety comes the concern for changes observed in the learning environment with growing police presence, and potential ramifications it poses on student mental health.

“I don’t think it’s had any positive impact on student outcomes,” Beers said. “Officers that are extensively there to keep safety [have] not yielded any beneficial results. As far as I can tell, and things that I’ve read, is that the presence of these officers have not reduced or eliminated these types of shootings. You’ve seen stories of officers arresting children, and stuff that used to be the responsibilities of teachers. [The] unfortunate ways policing is used right now, especially [with] minority communities and people of color, has had a negative impact on certain people.”

Entrenched in the polarities of the modern political climate, divisions are often worsened by social media. Though digital platforms host discussion with contributors of every background, hostility attached to these online environments render possibilities for civil interaction difficult. Beers believes parents are key in mobilizing the community, a step critical to spurring larger national awakening.

“These concerns certainly aren’t new,” Beers said. “This has been occurring for a long time, [and] it certainly has, multiple times in Texas. The thing to do, is of course, keep writing. Representatives should know that this is a concern amongst parents. We need to have our voices heard.”

Fellow Access RRISD Member Meenal McNary who is also a leader in the organizing groups Round Rock Black Parents Association (RRBP) and Anti-Racists Coming Together (ACT) shared similar sentiments.

“Both groups have fought against the formation of a police department in our schools, knowing full well how harmful police are to marginalized communities, Black and Brown children, children receiving [special education] (SPED) services, our Queer community, and then the intersection of all those,” McNary said.

Most recent data released by the district in November 2019 found that 0.8% of the total student population received in-school suspension, during which 2.2% of Black students and 1.9% of special education students also received in-school suspension. Key findings evidence that Black students, who made up 9.04% of the total student population of 51,807 enrolled in 2019, represented nearly 25% of all in-school suspensions assigned. Similarly, special education students, who made up 10.28% of the total student population, represented a staggering 18.48% of all in-school suspensions assigned.

“We have transitioned from SROs, who were harmful and have hurt children in our district, to a full scale police department, which we’ve spent millions on,” McNary said.

An Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion came to fruition in August 2020 following years of community input and research completed by a designated task force. Instrumental to aiding campuses develop actionable goals under a guiding ‘Equity Framework,’ proposing solutions to inequities faced by marginalized youth first began by analyzing the scope of demographic groups represented in the student body. Considerations made in this process were paramount to reinforcing the foundation for prolonged activity by individuals at all stages of school board involvement.

“Especially for our district, specifically town halls and the superintendent, who has been wonderful in meeting with different groups of people, knows how we feel about this,” McNary said. “He’s the one that puts people in place and makes innovative decisions to make sure that we are doing what we can to protect our students, and that gun violence is the last thing they need to worry about when they go to school. Gun violence should be the last thing I worry about when I send my child to school.”

For McNary, efficacy of leadership continues to remain synonymous with proximity to resources, a privilege that magnifies the changing landscape in which leadership operates and thrives. Come November, midterm elections will become center stage for those fighting for change in local office.

“I would love more access to the people that are in power making these policies,” McNary said. “Because oftentimes, those white men in power, they listen to their base who look and sound like them. And we can’t touch them. It almost seems inaccessible at times.”

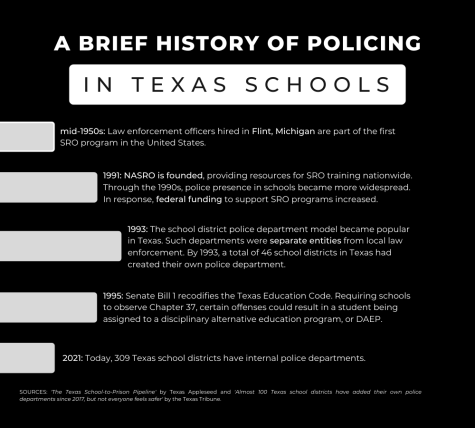

Officially finalized in February 2020, the resolution confirming the formation of the Round Rock ISD Police Department (RRISD PD) marked the end to a near three-year timeline to establish long term district safety and security. Inter-agency partnership between local law enforcement including the Williamson County Sheriff’s Office, the City of Round Rock Police Department, and the Austin Community College Police Department supplied school resource officers (SROs) to campuses until the last partnership terminated at the end of the 2020-2021 school year. The first RRISD PD officers were hired in September 2020, under the board’s “desires to employ commissioned peace officers” into a fully-operational police department as of June 2021.

Superintendent Dr. Hafedh Azaiez emphasized confidence in existing routines such as locking doors during the school day and employing video intercom technology to monitor visitor entry. Azaiez also noted plans to utilize an $815,311 grant provided by the Texas Education Agency (TEA) to install a bullet-resistant film on glass windows and doors in all elementary schools.

In the aftermath of the May 2018 Santa Fe High School shooting in Santa Fe, Texas, 17 laws were passed by Gov. Greg Abbott to address school safety. Particularly, House Bill 2195 (HB 2195) mandated active shooter training for school-stationed officers. Senate Bill 1707 (SB 1707) stated that all school district peace officers, SROs, and security personnel should refrain from practicing “routine student discipline or school administrative tasks” and avoid “contact with students unrelated to law enforcement duties.”

RRISD PD has stood by current procedures, which includes emergency drills, threat-assessment training, and the anonymous alerts app to report suspicious behavior. The police department did not return multiple requests for comment, but reposted recommendations in a statement shared by the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO). The association, which established the “triad” concept of school policing, attaches SROs to the responsibilities of teachers, informal counselors, and law enforcement officers.

“Carefully selected, specifically trained SROs can and have prevented and mitigated school violence,” NASRO said in their statement. “This includes intervening before violence begins and stopping it quickly when prevention was impossible. Every school at every level must therefore have a carefully selected, specifically trained SRO on its campus whenever school is in session.”

Significant reorganization of district administrative structures in November 2019 placed Behavioral Health Services under the Safety and Security Department, later followed up by a $1.17 million spending addition in August 2020 that was allocated towards hiring ten social workers to serve as district employees and five under contract. Two social workers were assigned to each vertical learning community, which comprises the five high school campuses and their immediate feeder patterns.

The current policing framework as such, takes on a “four-pillar approach” that focuses on “safety and security, equity, behavioral health, and student advocacy.” Westwood social worker Ms. Eden Males expressed appreciation for the consistency of district commitment to building a holistic understanding of student needs beyond academics.

“We work really closely with the police officers to make sure that we’re doing the best we can as a team,” Males said. “We usually do collaborate, especially if there is a potential for there to be a mental health or behavioral component to it, just to see how we can better support the student and the family in navigating that.”

As clarified by RRISD, using the term ‘behavioral health’ is preferred in reference to both “mental health and substance use treatment and services.” Employing a multitude of perspectives that aid in providing specialized support for student emotional and physical wellbeing, a social worker’s role on campus transcends the responsibilities attached solely to crisis de-escalation. Approaches that consider the multicausality of the circumstances contributing to student behavior can offer a perceptive value in larger discussion of gun violence prevention in schools.

“When we look at the individual as social workers, we’re looking at them from a biopsychosocial model,” Males said. “So that’s looking at things biologically [and] psychologically, [with respect to] their thoughts, emotions, behavior, and then also that social component, [including] their socioeconomic status, socio-environmental [factors], and cultural dynamics.”

Males cites the commitment to relationship-building with students as a key facet of success prioritized in the model, a step many times led by the police officers themselves before involving campus social workers in particular cases. Additionally, all officers complete mental health training in conjunction with their work alongside licensed professionals.

“Having those different perspectives with such a sensitive topic is so important,” Males said. “We need that multidisciplinary approach [when] looking at individual educational backgrounds differently to make sure we’re not missing anything and doing everything we can to support our learning community.”

The sustainability of measures taken to mend disciplinary systems perpetuating exclusionary practices among students of color continue to raise questions on the very nature of policing in schools and the glaring disparities that plague progression towards equitable learning.

“As a department, we focus on what we can do to collaborate to reduce that school to prison pipeline,” Males said. “Speaking to increased police presence, I think any increased student support on campus is something that we can all benefit from.”

Response to a nationwide epidemic of gun violence has come to form a wholly unique, yet fractured portraiture of organizations at the intersection of disciplines seeking to collaborate in not only protecting students from future tragedies, but supporting them in continuous discussion.

But where elected leadership falls short, voices advocating on behalf of their respective campuses and the needs of the larger youth collective offer a perspective shaped by the condition of institutional factors outside of their control—a perspective often lauded—but rarely acted upon meaningfully.

Nitya Khurana ‘24 is one of 17 students who form the district-wide high school advisory team known as VOICE. Aiming to gather feedback from peers on their respective campuses and communicate such suggestions to the Board of Trustees and Superintendent, program participants have led discussion on subjects ranging from dress code requirements to student safety. In reflection of recent events, Khurana acknowledges implications in the calls to implement stricter security measures.

“It’s really easy for anyone to get in the building,” Khurana said. “There’s not really a way to address this in terms of infrastructure. [If using] student IDs [as a security measure], it’s easy to forget them, [and] you [may] get locked out for the whole day. One way they could [address the issue] is potentially having more police officers, but that would bring up another safety concern about those police officers [having] guns, and it’s not a given that you can trust them.”

Although concerns related to campus safety in the event of an active shooter have not been explicitly discussed by VOICE members this past school year, other topics receiving significant district investment in recent years have seen the mark of student input.

“We’ve actually discussed mental health a lot,” Khurana said. “That’s a huge priority especially now, [as] it’s on the uptake that people are talking about it, and more people are getting the help they need.”

In recognizing the power relationships that govern education, it is the insights of students that acknowledge the shortcomings of public policy while magnifying vital necessity for more.

“Despite having this student leadership group, I think a lot of student voices are still missing,” Khurana said.

Class of 2023

Ardent advocate of em dashes, pastel cardigans, and above all, the written word. Amoli and I are honored to lead a publication by students,...