Class of 2023

Welcome to the Horizon! I am looking forward to leading this wonderful team of reporters and editors with Catharine. Outside of the newsroom,...

April 11, 2023

A student furtively glances around a brightly lit classroom. Pulling out a phone under the cover of tall privacy shields, he quickly snaps a picture of the test. Later, he might trade his picture for a picture of another exam, or post it on a hidden Discord server for multiple students to access. No matter the method, a number of students in subsequent blocks will have an unfair advantage.

This is not the only type of academic dishonesty that occurs at Westwood. Ranging from discussions about exam questions to receiving entire tests over social media, cheating has become more frequent and creative in every type of class. The current consequences introduced by the district, administrators, and teachers have done little to deter the student population from engaging in academic dishonesty.

“The consequences haven’t necessarily fixed anything,” Assistant Principal Bradley Walker said. “Because at the end of the day, that [student] will choose to do whatever, whether they get a consequence or not. I can give one kid a warning, and they will never cheat again, and I can give a kid [In-School Suspension], and they will still cheat.”

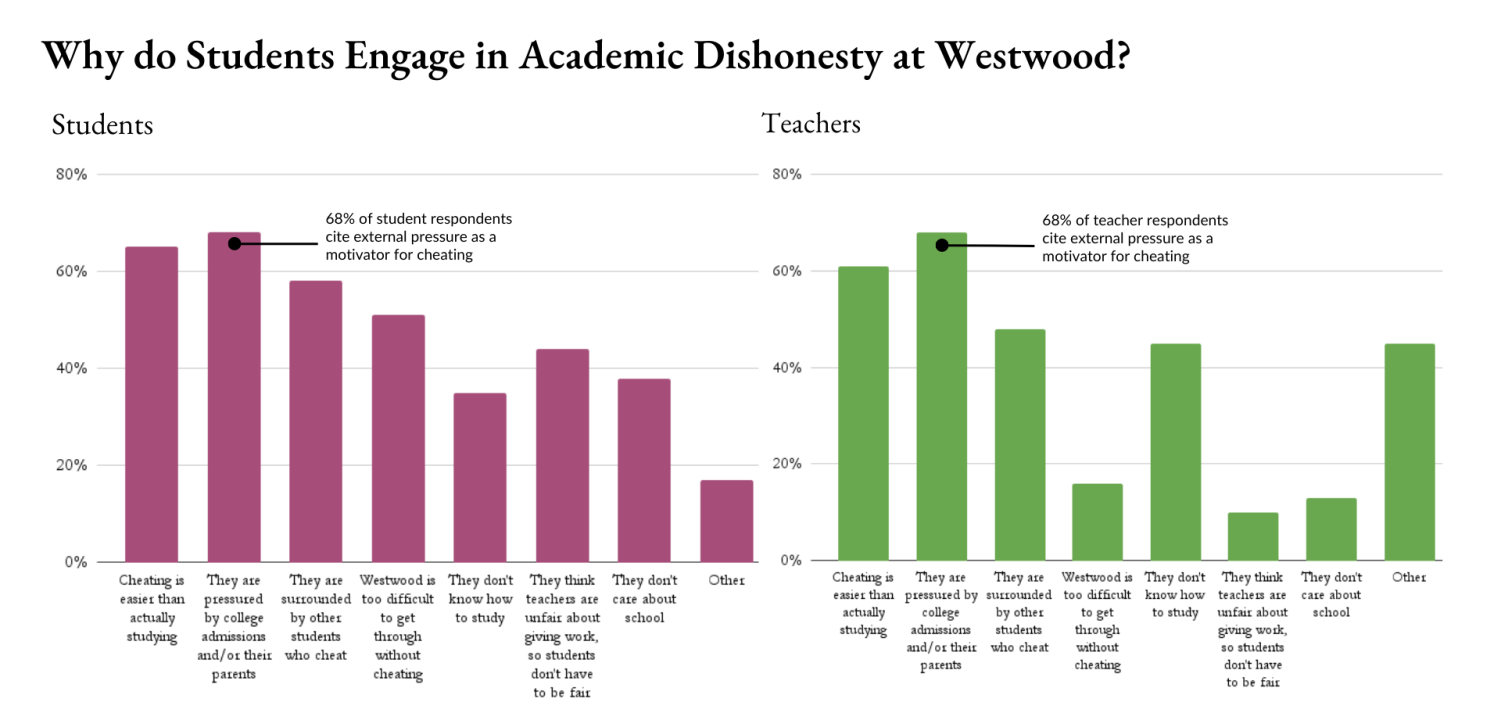

Student and staff surveys conducted by Westwood Student Press through email yielded 212 student responses and 31 teacher responses in a period of 3 days. The survey revealed stark contrasts between student and teacher opinions, but also surprising points of agreement in terms of consequences and solutions.

In Round Rock ISD (RRISD) policy, “academic dishonesty” constitutes any form of malpractice (receiving unauthorized help on individual assignments to gain an unfair advantage), collusion (assisting someone to cheat), plagiarism, copying, exam cheating, duplication (submitting the same work in different courses), falsifying data, and falsifying documents. When asked to give a personal definition of “cheating,” most students gave far more lenient definitions than teachers.

“Asking if the test was hard isn’t cheating because the advantage isn’t major, and ‘cheat sheets’ of formulas aren’t cheating as long as you show work, because the test isn’t a memory game, it’s a test of application,” one anonymous student said.

The definitions of academic dishonesty provided by students demonstrate a lack of consistent knowledge as well as an acceptance of certain forms of cheating in daily academic life. Questions such as “How was the test?” and “How much do I need to study?” often serve as conversation starters in the hallways, but many of these seemingly harmless inquiries may turn into “There were many hard questions about topic X,” or “I found the entire test on this website.”

“I have asked people things like ‘What was on the test?’ or ‘What should I study?’ and honestly I would keep doing that,” an anonymous student said. “I feel a little bad, but to me it’s worth it to keep my grades up. I don’t really consider those questions punishable offenses nor do I think that there’s any way my teachers would find out. I’ve also googled questions while taking a test, and so far I haven’t been caught, but I’m more hesitant to make [that] a habit.”

When asked to suggest scenarios when cheating may be considered ethical, many students mentioned circumstances where the student would otherwise fail. On the other hand, the majority of teachers came to the conclusion that cheating is inherently unethical, and no circumstances merit dishonest behavior.

“I’m far more understanding of people who might steal food or money, because they actually need those things to survive, than someone who steals a grade for an assignment because they didn’t want to do the work or because they didn’t want to suffer the penalties for not being honestly prepared,” an anonymous teacher said.

According to RRISD policy, when a student is found guilty of academic dishonesty, their teacher must submit a referral form and contact their assistant principal and parents. The student would receive a “0” on the assignment, and their teacher would decide if the student can earn back credit. The assistant principal must also inform the student’s other teachers and activity sponsors, and determine if the student should receive additional consequences. These additional penalties include Saturday School, suspension, and reports to colleges during the college application process.

“We address every situation,” Mr. Walker said. “We follow RRISD academic dishonesty policy, but as far as consequences, it can look different. We consider all the facts, how many people are affected, and we find out if there are multiple people involved. We have flexibility to get creative with things and figure out what we feel would be the best way to remedy this problem, [because] sometimes there is no black and white. But we don’t like to make knee-jerk reactions to something before having all the information.”

When teachers take cases to the administration, the assistant principals operate on a tiered system, where each repeat offense merits a more severe consequence. However, teachers sometimes choose to handle cases on their own. Some are lenient for the first offense, some refuse to write letters of recommendation, and some have in-depth conversations with students to understand their reasons.

“If I knew that all other teachers were following the district policy, I would follow the policy,” one teacher said. “Since I am not confident that teachers enforce the rule in accordance with the policy I handle each incident on a case-by-case basis.”

Additionally, five teachers expressed that problems exist with enforcing consequences.

“The policies are fine,” Spanish teacher Luisa Rice said. “The problem is that we need to implement them. Some teachers don’t want to deal with it and ignore the cheating in class. Some parents find all kinds of excuses to protect their kids. Some AP’s just don’t want to deal with it or the parents.”

Students are also generally unaware of the consequences for cheating, making them more inclined to engage in such behavior given that the benefits appear to outweigh the potential risks.

“[I’ve] known some people who’ve been caught cheating several times in the highest level classes, and only got off with a slap on the wrist, a redo, and sometimes a zero, no referrals,” an anonymous student said.

In addition to inconsistencies in enforcement, the policies for public schools tend to include less strict codes of conduct than private schools, limiting suspensions or expulsions to specific acts of assault or threats rather than extreme cases of academic dishonesty. For most universities and private high schools such as the Kinkaid School in Houston, TX, the penalties are much more severe for students who cheat.

“Your case would be presented to the Dishonesty Council,” Kinkaid graduate and current University of Texas at Austin student Ryan Karkowsky said. “There’s a combination of students and adults that talk about your case, and think about what your punishment should be. They think about what you’ve done in your current environment, how much of a negative effect it had on others, and how much of a benefit it gave you. The punishment is usually an In-School Suspension. But for repeat offenses, you’re kicked out of the school.”

While expulsion may not be possible in a public school setting, certain changes have been suggested to hold dishonest students accountable and discourage others from cheating. The most common solution put forward by students and teachers alike is maintaining consistency and ensuring awareness.

“The consequences, in my opinion, should be standardized across all students,” an anonymous student said. “Currently, I feel that some of these consequences are only applied based on the personality, beliefs, and teaching style of the teachers, which can potentially encourage cheating. The consequences for academic dishonesty should be made clear across ALL classes and applied in a more regulated manner.”

One of the most subjective consequences is reporting academic dishonesty to colleges. Though RRISD policy dictates that counselors must report cheating incidents to colleges, many colleges do not have specific sections that require such a report, and those that do often contain vague language such that counselors may or may not feel inclined to disclose the information in a way that harms the student applying.

“Maybe marking the student’s file such as the transcript that a college admissions person will view [will help],” an anonymous student said. “This suggestion would probably [be] best if this student has multiple incidents of cheating throughout the course of high school. Westwood students work hard in order to get into prestigious colleges. Knowing that their cheating can hinder their ability to get into college may make a bigger impact.”

Additionally, proactive efforts to curb cheating such as creating harder tests often end up harming students who don’t cheat far more than students who regularly engage in academic dishonesty. These instances usually have little impact on the root of academic dishonesty itself.

“In [marking period 2] the Advanced [Precalculus] teachers made the last test before midterms way harder because so many people were cheating,” one anonymous student mentioned. “The thing is – people cheated on that too, and most others had a failing raw score. To fix that [the teachers] added a curve, and practically everyone who cheated got a 100.”

Though there may be quick solutions to reduce the scale of academic dishonesty temporarily, such as increasing the harshness of consequences, the reality is that a systematic change may have to occur to eliminate cheating completely. Many students who usually score well cheat to get the perfect 100, indicating that the way GPA is calculated at Westwood encourages even more academic dishonesty.

“At Kinkaid, there was an 11.0 scale,” Karkowsky said. “12.0 is an A+, 11.0 is an A, 10.0 is an A- and so on. What was interesting about the grading is that they averaged the two semesters, and that’s what went on your final transcript. So if you got an A+ first semester, you only needed an A second semester to average an A+. There was definitely competitiveness, but I didn’t see it as getting more people to cheat. It was more like studying for an extra hour to be better than someone else.”

Along with a letter-based grading system, Kinkaid incorporates more essay-style exams and projects where access to internet resources is unlimited, minimizing opportunities for academic dishonesty.

“In the real world, you’re going to have a giant array of resources that you can take advantage of,” Karkowsky said. “If you’re trying to force people to take traditional tests, I don’t know if that’s necessarily preparing [us] for our future careers and lives. Maybe the answer to the cheating problem all over is to get rid of tests, [and] transition classes to more discussion-based things, more writing, speaking, and presenting, because those are the skills that you’re going to have to have anywhere you go in life. So if you kind of try to get that instilled in everyone at an earlier age, maybe that’s maybe that’s the answer.”

Karkowsky also mentioned the difficulty of success in college if a student habitually participates in academic dishonesty.

“At UT, you have to think creatively and [the assignments] are more based on how you answer a question rather than what the actual answer to that question is. There’s no right answer, [and] you have to kind of figure it out on your own. [For] a lot of the writing assignments [and] analyzing, you can’t just do that if you haven’t been practicing it in the past honestly.”

As teachers and administrators hunt for solutions, the culture of academic dishonesty developing at Westwood has continued to damage and frustrate students who don’t cheat.

“Those who actually try and work hard are demotivated and discouraged,” one student said. “And they fall prey to the rank system that others cheat to get on top of.”

The issue of academic dishonesty has forced teachers to modify their assignment methods. To prevent cheating, they have started creating multiple versions of tests, assigning paper-only tasks, using free response or project-based assessments, implementing classroom phone bans, and other actions.

“Cheating is exhausting,” an anonymous teacher said. “It’s exhausting to anticipate it, to plan around it, to question it, to see it, to interrogate students about it, to write referrals for it, to call home about it, etc. I understand and can sympathize, at times, with students who choose to cheat, but I wish that students would think about it from the teacher perspective too.”

While no school can control every individual student decision, creating strong, consistent policies and enforcing consequences could be the first step to battling academic dishonesty. In the long run, public schools like Westwood require sustained conversations between parents, students, teachers, and administration to address this issue at its core.

“Cheating is theft,” an anonymous teacher said. “It robs teachers of time better spent on actually educating students. It steals away our trust and respect for one another. It steals someone else’s intellectual property. It takes aways from our school’s reputation and erodes our school’s culture.”

Class of 2023

Welcome to the Horizon! I am looking forward to leading this wonderful team of reporters and editors with Catharine. Outside of the newsroom,...

Mitchell Cone • Apr 19, 2023 at 1:10 pm

I’m in all advanced classes (where most of this happens), and I can definitely tell you that accountability for cheating is a joke. Nobody ever gets caught, and even if they do, the punishments are essentially meaningless. This is such a pervasive problem at this school, such that I, with somewhere in the neighborhood of a 5.3 GPA, am barely even in the top 50%. I feel like the automatic admission policy that they have at UT definitely doesn’t help, but a lot of this comes down to pressure from parents on their kids to perfect grades. Good grief, advanced/AP/IB classes are supposed to be HARD, If everyone gets a 100, then something’s wrong. Anyway, they need to increase ,or at the very least, actually enforce the penalties.

Avi Rajesh • Apr 14, 2023 at 8:20 pm

This was amazingly written!!

Scott Seamon • Apr 12, 2023 at 8:34 am

Such a great story! Cheating really has gotten bad here, glad people are finally talking about multiple sides of it instead of just complaining “cheating is bad” and calling it a day.