What You Need to Know About the Holocaust

Bettmann/CORBIS

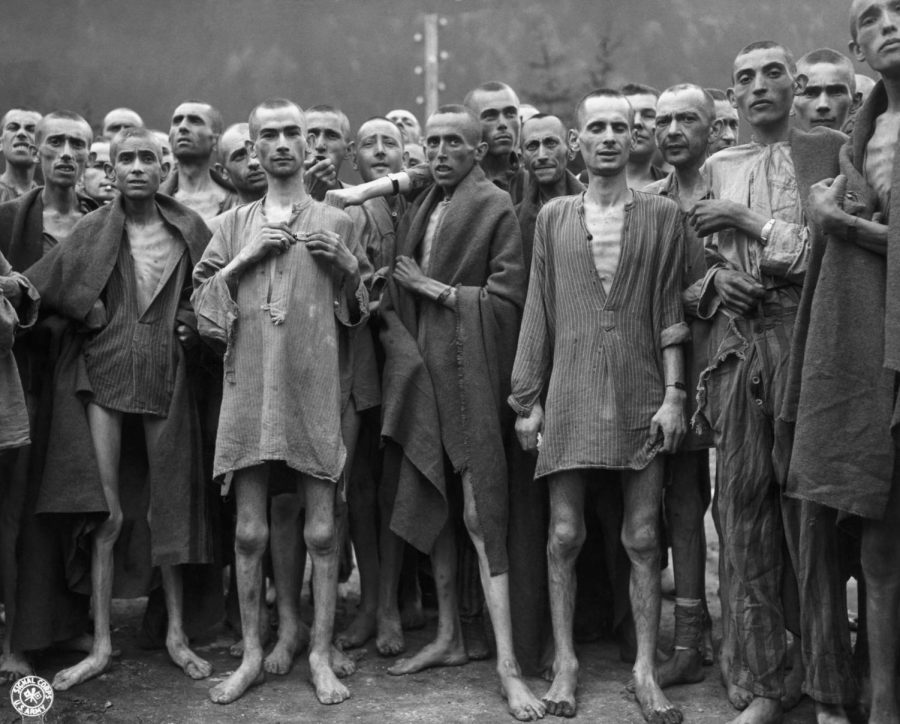

Survivors of the camp in Ebensee, Austria photographed on May 7, 1945, just a few days after their liberation.

October 27, 2020

The systematic genocide of millions of European Jews during World War II is what is now infamously remembered as the Holocaust. The Nazi regime executed these killings between 1933 and 1945. Hitler, the leader of the Nazi party, saw Jews as an inferior race and “Lebensunwertes Leben” — “life unworthy of life”. Approximately six million Jews and five million other targeted minorities died in the years of the Holocaust.

“The Holocaust wiped out many of the most educated and productive people in Western Russia,” David Florence Prof. of Government at Harvard James A. Robinson said. “It was a major shock to the social structure of the invaded regions, dramatically reducing the size of the Russian middle class. We find a robust relationship between the decline in Jewish populations and subsequent economic development”

Amongst the other targeted minorities were Romani people, intellectually disabled, dissidents, and members of the LGBTQ+ community. Hitler was obsessed with the idea of maintaining the pure German race, or “Aryan” race. He used the term “Aryan” to describe his ideology of racial supremacy that classified those with blond hair, blue eyes, and tall height as the “ideal human”. When he was appointed as German Chancellor in 1933, he focused his efforts on achieving racial purity.

“The Aryan myth is now completely discredited among scholars,” psychologist Knight Dunalp said in his book The Great Aryan Myth. “Ethnologists (outside of Germany) do not speak of an Aryan race any more than they speak of a Jewish race.”

Jews and other targeted groups were murdered by death squads called “Einsatzgruppen” — “operational groups”– or sent to extermination camps and concentration camps. Concentration camps were primarily used to inhumanely confine whoever the Nazi regime saw as a “security threat”, exploit prisoners for slave labor, and to murder individuals. Extermination camps were oriented solely to kill prisoners. People were murdered either by asphyxiation with the poison gasses Zyklon-B and chemically pure carbon monoxide or by shooting.

“To see it with my own eyes was really a terrible shock,” survivor of The Płaszów camp Toby Biber said, “and I can tell you one thing, that there is a point in your life where your heart is not a heart anymore, it’s a piece of ice. I had the feeling that my heart was hard, and not because I didn’t have feeling for my fellow prisoners – no, that I always had – but there was this hand, this iced hand which kept hold my heart like this. And my heart was not alive anymore, it was – the sheer terror of it made part of my body almost turn into the ice”

Auschwitz, or Auschwitz Birkenau, opened in 1940 and was the largest of the concentration and extermination camps. Located in Southern Poland, Auschwitz functioned as both a concentration and extermination camp. Some prisoners were also subject to barbaric medical experiments and examinations led by Josef Mengele. Mengele became known as the “Angel of Death” for his inhumane experiments which included injecting serums into the eyeballs of children to study eye color, and everything from blood transfusion to limb amputation of twins in an effort to study them.

“If Auschwitz … stands as a symbol of the Holocaust,” American historian David Marwell said, “Then Mengele, as perpetrator, has come to serve a similar role for the death camp… At some point, he emerged as the embodiment not only of the Holocaust itself but also of the failure of justice in the wake of the war.”

Auschwitz played such a large role in Hitler’s “Final Solution“ because of its proximity to a railway junction with 44 parallel tracks. The railway was used to transport Jews from throughout Europe. Once prisoners arrived at the camps they underwent a process called Selektion which determined what sector of the camp they would be sent to. The young and physically fit were sent to work. Young children, mothers, and the old and sick were sent directly to the gas chambers, and a few selected for the medical experiments. In 1944 Italian chemist Primo Levi arrived at the camp along with 600 other Jews. He survived to tell his account of the Selektion.

“They [SS men] seemed simple police agents. It was disconcerting and disarming,” Levi said. “Thus in an instant, our women, our parents, our children disappeared. We saw them for a short while as an obscure mass at the other end of the platform; then we saw nothing more.”

By late 1944 and early 1945, it was clear that Nazi Germany was close to defeat; its military force was declining and Nazi troops were forced to retreat. To remove traces of killing operations, prisoners were forced to cremate corpses and guards destroyed parts of the camps before abandoning them. Allied forces began moving across Europe and liberated concentration camp prisoners they encountered. SS guards transported inmates by train or forced marches, also known as “death marches”, to try and prevent the liberation of an even larger number of prisoners. These marches ended May 7, 1945, when German armed forces officially surrendered to the Allies.

Survivors of the camps found it hard to return home as hundreds of communities had been completely destroyed, and more than 250,000 of them found shelter in displaced persons camps. Some displaced Jews emigrated to nations in Europe and others settled in the U.S. A significant number of survivors also moved to the soon to be established state of Israel. Today, Auschwitz is open to the public as the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum along with hundred of memorials across Germany as a reminder of the genocide and in honor of its millions of victims.