‘Minari’ Explores Korean American Roots

@minarimovie

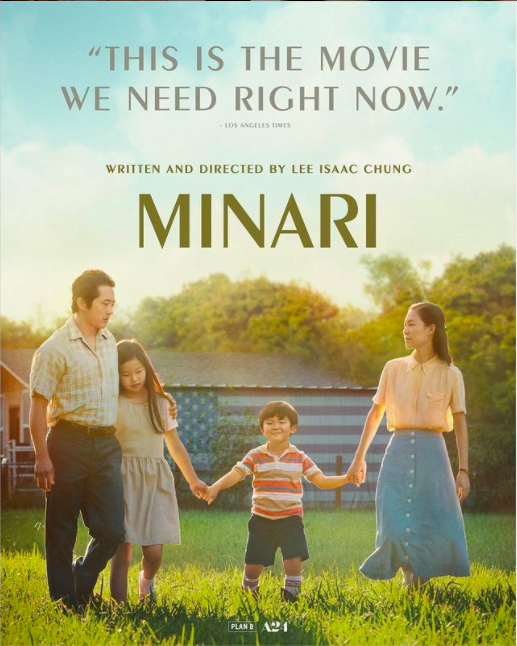

Lee Isaac Chung’s ‘Minari’, starring Steven Yeun, Han Ye-ri, Youn Yuh-jung, and more, beautifully captures the Korean American experience. Photo courtesy of @minarimovie on Instagram.

April 29, 2021

Minari (2020), directed by Lee Isaac Chung, received numerous awards in the past few months, but not without being subject to controversy. The Golden Globes recently received criticism over the film being nominated in the Foreign Language Film category, despite being set in America and being directed by a Korean-American. Interestingly enough, Minari has been nominated for the Best Picture category for the 93rd Academy Awards instead. The film itself should prove why the latter nomination was the more accurate choice.

Minari tells the story of a Korean-American family that has recently moved from California to Arkansas. The father, Jacob, is excited to fulfill his dream of becoming a successful farmer, but his wife Monica is less optimistic, and their children Anne and David anxiously watch the tension between the two increase.

The neutral atmosphere and realistic dialogue make the film almost tangible, but the skillful artistic choices of the director are visible as well. For example, the main family is deliberately structured to showcase the dynamic between different generations; Jacob and Monica are first-generation immigrants, while Anne and David are second -generation Korean-Americans who were presumably born in California. Jacob and Monica represent immigrants’ conflicting desires for success and stability, with Monica concerned that Jacob has lost focus of why they came to America in the first place: to have a secure future. The subplot of the movie explores David’s relationship with his grandmother Soon-ja, who has lived in Korea all of her life. He initially dislikes her due to her unfamiliarity with American culture, but gradually comes to accept her.

The most impressive aspect of the film, at least for me, was the subtle touches of Korean-American culture and attitudes. Monica sheds tears over her mother bringing gochujang, or pepper paste, from Korea, and shrinks away from overly friendly white churchgoers. The children speak Korean to their parents but speak English between themselves, which is common in most Korean-American families. David mentions that his grandma “smells like Korea”, and I was immediately overcome with a sense of déjà vu. It’s a phrase all second-generation Korean-Americans will recognize, though it’s impossible that we have all smelled the same scent before.

Such details will not be particularly impactful for every audience member, but they left a lasting impression on me as a Korean-American. Minari was carefully constructed so that it would resonate deeply with Korean-American viewers, without alienating those who do not speak the Korean language.

Speaking of language, I’ve seen many critics mention Parasite (2019), directed by Bong Joon Ho, in their reviews of Minari. This is probably due to the fact that both films garnered attention over their use of subtitles and ethnically Korean cast members. While such similarities are definitely present, I think it is important to understand that Minari is not a Korean film, but a Korean-American one.

The subtitles in Parasite are there so the audience members can overcome a language barrier, but the subtitles in Minari are an artistic element. The latter emphasizes the bilinguality in actual Korean-American families, and shows the difference between their interactions with Koreans and non-Koreans.

Minari is a beautiful film that explores the newly found turmoil a Korean-American family experiences in America, though they have been living there for over a decade. I recommend this movie to all Americans, but particularly those who come from immigrant families.