New York Times Film Exposes Ongoing Streak of Unethical Journalism

j4p4n

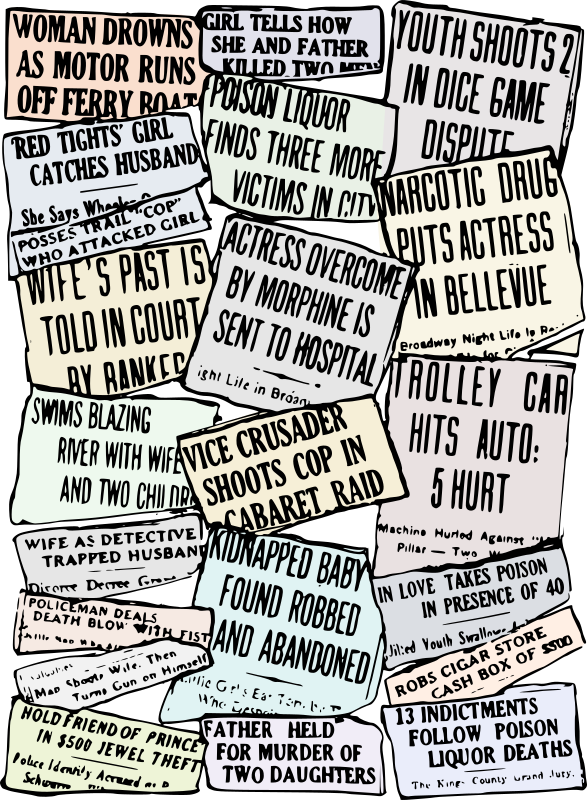

The New York Times needs to know when they are overstepping society’s boundaries. Photo courtesy of j4p4n.

October 14, 2021

One YouTube comment sourced from the “dark web” should not have been enough to convince an increasing 13,000 viewers that the New York Times (NYT) had murdered an anonymous interviewee three years ago. However, given how poorly the subject’s identities were censored, it wasn’t an unbelievable claim.

The video in question, titled “What it’s Like to Grow Up in the Narco Zone,” was created by Mexican journalists who sought to show how children in an elementary school had been affected by local drug-dealing gangs, some of whom were relatives of these students. Although sharing sensitive information like this put the teacher and student interviewees’ lives at stake, director Everardo González chose not to blur their faces. Instead, the only covering he provided to the subjects were white caps akin to wrestler masks for “anonymity, and partly as an eerie aesthetic choice.”

Anonymity is a severe overstatement; the masks had ear, eye, nose, and mouth holes where all main facial features were clearly visible, and many of the students’ hair stuck out from the bottom. The children appeared to be wearing their school uniforms with a legible patch left uncensored. The camera often zoomed in on their faces. Worst of all, voice editing was entirely absent from the film. Because the video was intended to frighten viewers, it distorted the information being given and prioritized visuals over the subjects’ safety.

You’d expect that a news site with 150 million global readers would acknowledge how this defies ethical journalism. According to the Society of Professional Journalists, news is meant to “balance the public’s need for information against potential harm or discomfort.” Ironically, it was an employee from the NYT that supported this idea when she wrote The Tricky Terrain of Virtual Reality in 2015.

“If the Times is going to help lead the way in using this new technology [virtual reality], it should do the same for grappling with the new ethical considerations,” NYT Public Editor Margaret Sullivan said in the article.

So then, how did an opinion documentary like this get published after an extensive process of editing where it could’ve easily been censored, and why hasn’t it been deleted after all these years? When users realized this, their comments quickly rose to the top of the page, one such being by YouTube user Julie Waninger.

“I never realized the New York Times killed the poor teacher because they didn’t censor her voice,” Waninger said.

It didn’t go unquestioned by hundreds of other curious viewers, but the only argument to support Waninger’s claim was that some had witnessed a video of the murder on a fictional, unlinked website. Google showed no results for the crime. While it was possible that the interviewee had been killed, it was more likely that viewers were misinformed. The rumor became viral almost two years after the video’s publication, and González’s video now has around 9,000 dislikes, including mine.

The NYT is not at fault for their viewers’ misleading comments, but what is troubling is that even after so long, none of the staff members have made an effort to protect viewers who are vulnerable to them. While most NYT employees are not expected to review audience feedback, anyone with an online presence acknowledges the impact of comments on a global social network and how easily they can gain traction. Staff involved with any publication should be held accountable for clarifying the truth when it is misconstrued by viewers, or at the very least disabling comments to prevent further spread of misinformation.

Because of the NYT’s failure to address comments like this, they continue to threaten the safety of interviewees today. Just a month ago, an appalling gif of equal unethicality was uploaded to their YouTube channel’s community page. The completely uncensored footage featured Seema Rezai, a professional boxer influenced by the Taliban’s rule in Kabul, Afghanistan. Like the so-called “murdered” teacher in Gonzalez’s film, she wanted to speak against the conflicts she faced in her city.

“Sharing this [information] is very dangerous for me,” Rezai said. “But I have accepted this risk because we will no longer sit silently.”

It would have been easy to ensure Rezai’s safety by censoring her name, blurring her face, and pitching her voice down, but the NYT decided against it, as usual, preferring the product over the person.

There are times that journalists may overstep society’s boundaries to provide vital information to the public. These are not those circumstances, especially when the effect of the news has an arguably lesser significance than the threat it causes to its participants. Journalism is generally defined by a desire to protect the public. The NYT, in that sense, is an outlier.