The Faces of Resilience and Routine: Custodians Care for Westwood Like Second Home

Sustained staffing shortage tightens community within custodial team

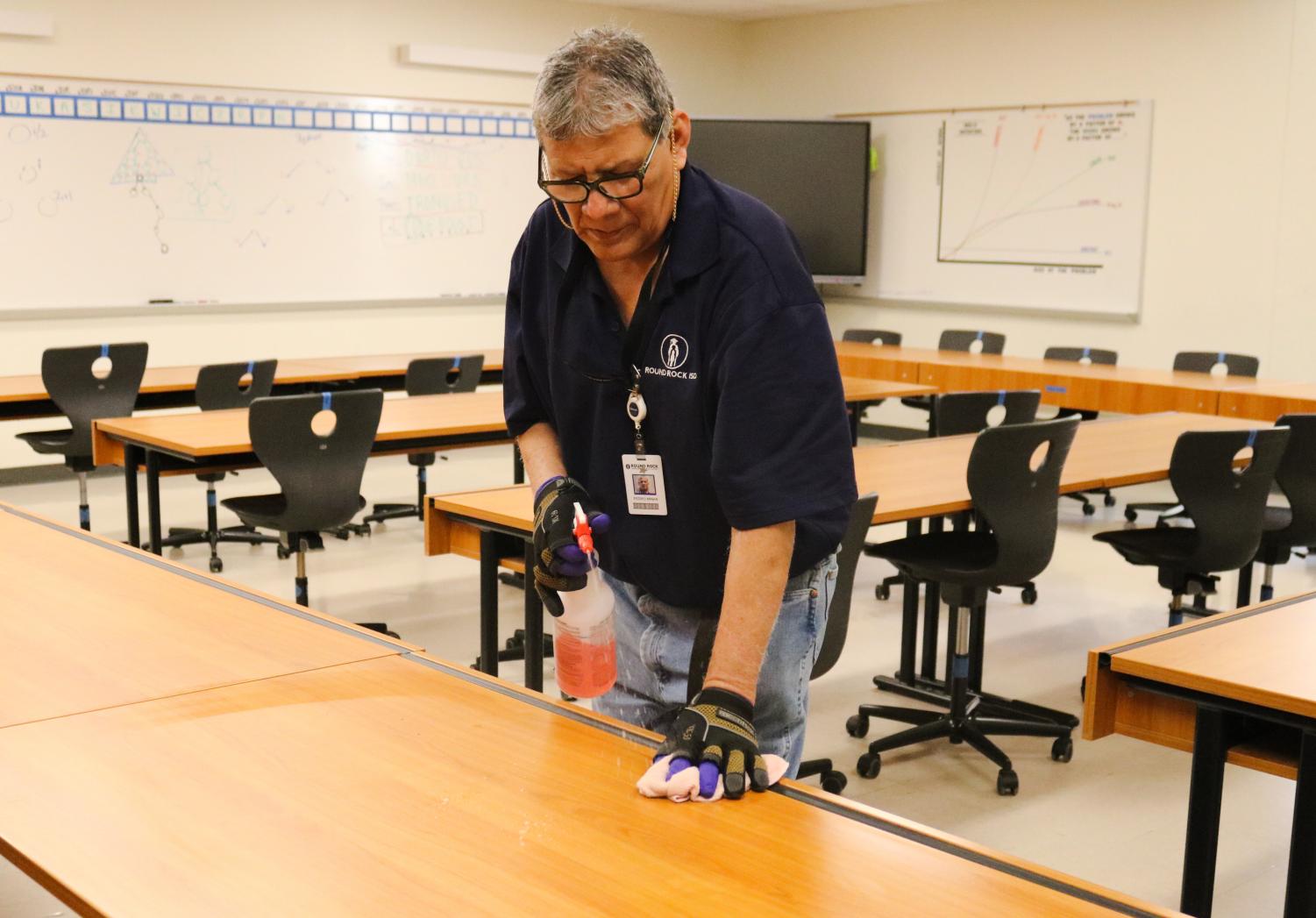

Clocking in at 7 a.m., Michael ‘Mike’ Apodaca has already walked most of the Westwood grounds before the first teachers and students trickle into the building.

Not far away, Luz Sanchez has also arrived for the day, along with Raymundo Vega. Together, they are the only three custodians working full eight-hour days in the school. The reality Apodaca points to is persistent and compounding.

“Nobody wants to be a custodian,” Apodaca said. “Because [it doesn’t] pay.”

At RRISD high schools, the demand for custodial staff is especially great. Apodaca also attributes the shortage to the popularity of opportunities at elementary schools, where the workload is less demanding across a smaller campus size, and starting salary of $15 per hour is consistent.

While the district has implemented strategic incentives to attract prospective employees, the auxiliary staff who constitute the custodial, nutritional, and transportation departments often cannot keep up with increased costs of living as attributed to the pandemic, and on a larger scale, the growth of the greater Austin area.

Neither this, nor arthritis in Apodaca’s knee causing his limp are causes for complaint. After nine months of working at Westwood, each task is ingrained like it was on the very first day.

“There are some students that talk to me every day,” Apodaca said. “When I’m tired, that gives me energy and keeps my hopes up. I’m always happy.”

There are some students that talk to me every day. When I’m tired, that gives me energy and keeps my hopes up. I’m always happy.

— Michael Apodaca

The 9:05 morning bell punctuates the sound of running water from the custodial closet. Flat mop in hand, Apodaca trails the last stragglers heading to class—debris already accumulating from underneath the microfiber bristles.

He fronts the F-hallway with a warm ‘good morning,’ nodding to staff while turning the corner. Quick to strike up conversation, he makes the rounds, listening for the next holler of his name.

“Everybody calls me Mr. Apodaca,” he said.

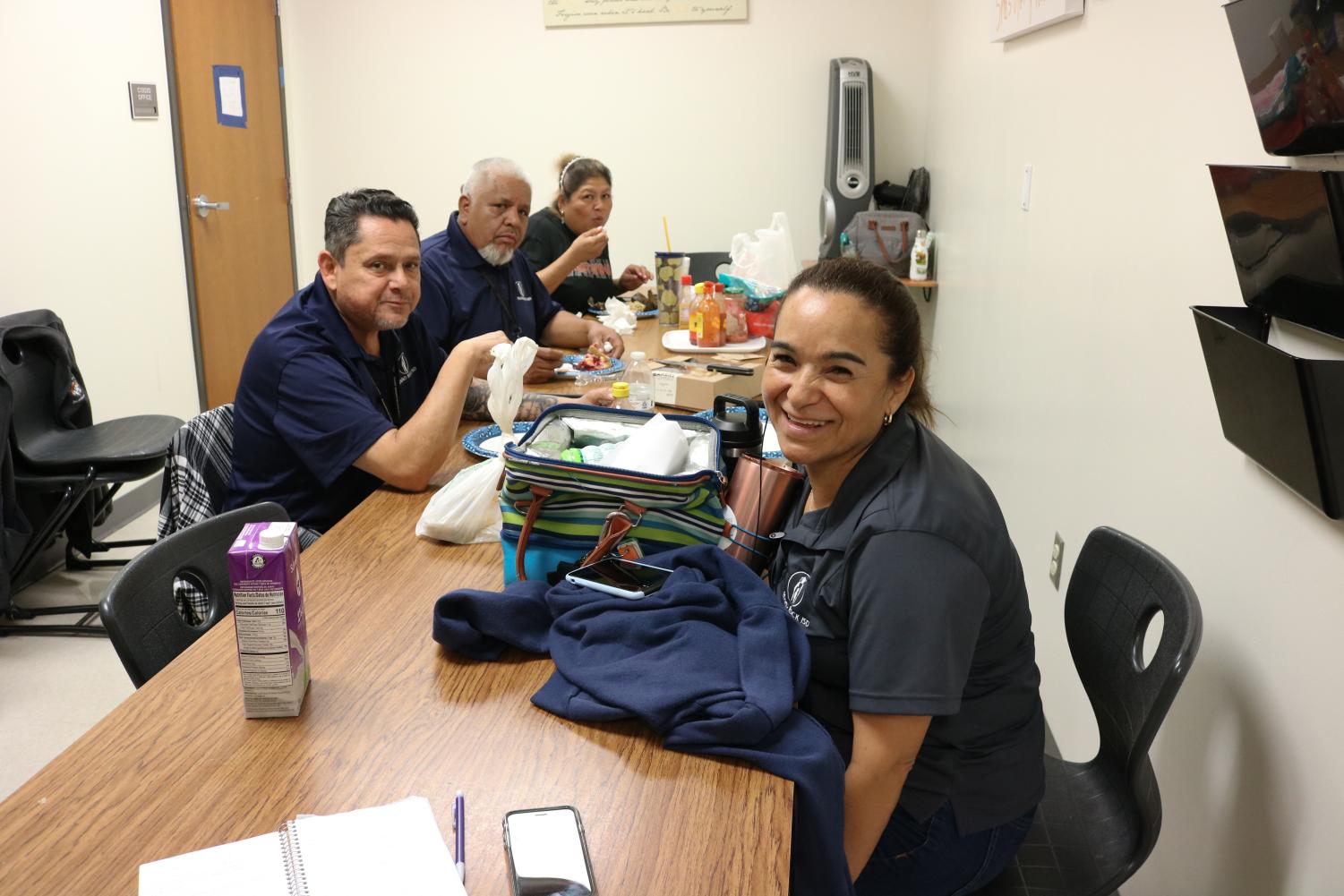

Now Apodaca’s day has truly begun. Joining Sanchez and Vega back in the cafeteria, the job is never a solo endeavor.

Vega, a Westwood employee of 10 years, brings the perspective of seniority and expertise. With a significant number of the custodial staff coming from a Spanish-speaking country, the common cultural background lends itself to more meaningful self-advocacy in the working environment.

Increasing visibility for their work starts with highlighting the in-between.

In-between scenes of the school day. In-between jobs. And in-between languages.

“I am from Mexico, others come from Honduras, Cuba, and they suffer differently than others,” Vega said. “Everyone suffers when you arrive here in the United States.”

Often negative perceptions of custodial duties inform reckoning with a job that inherently involves less interaction with the school community. Less than 20 total custodians field a campus of nearly 3,000 students.

Compounding this disconnect, what is left unseen is seldom acknowledged.

“People do not value our work,” Sanchez said. “[That is to say,] the students do not recognize our work.”

People do not value our work. [That is to say,] the students do not recognize our work.

— Luz Sanchez

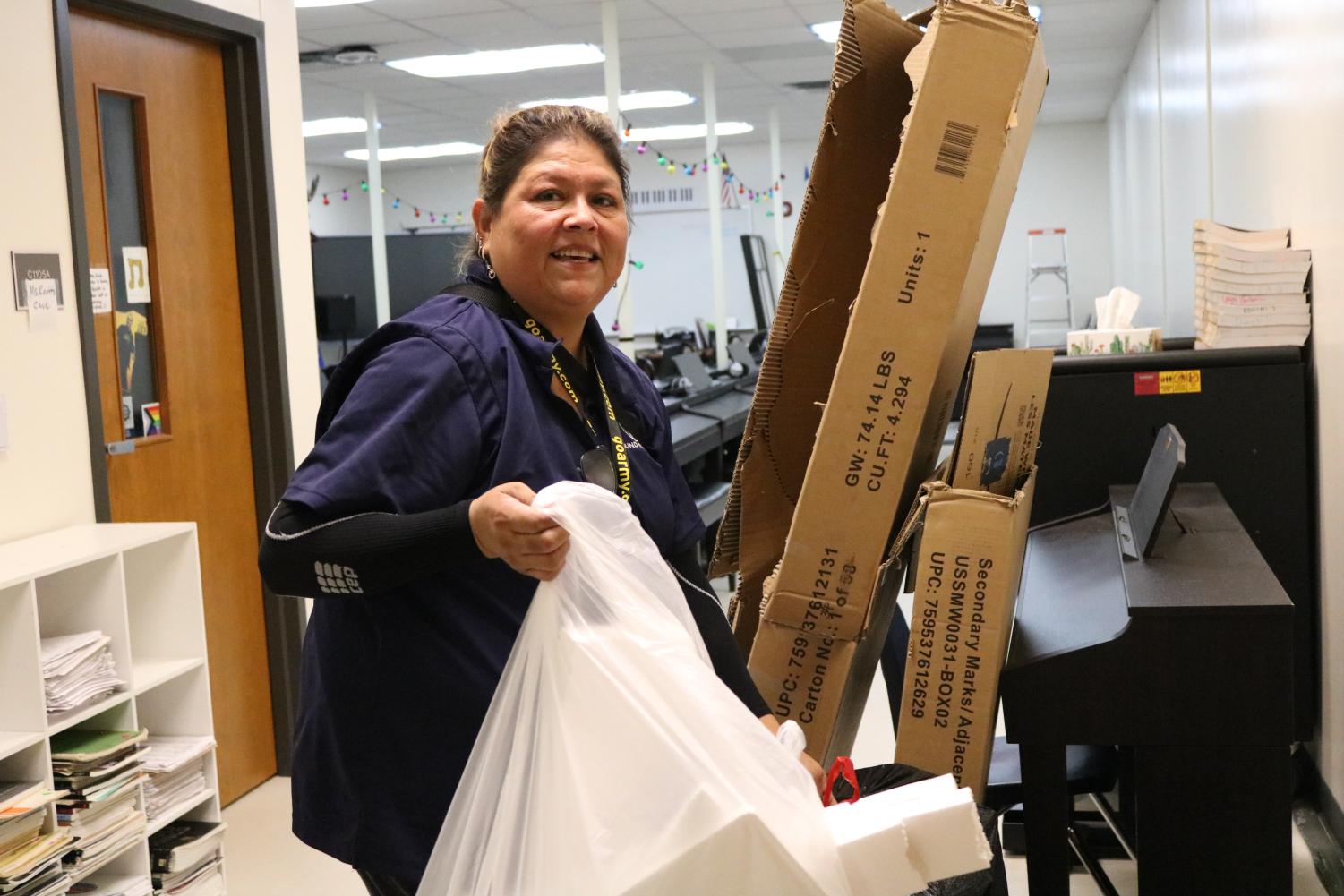

Serving as temporary lead custodian, Sanchez oversees the cleaning procedures at Westwood, but also spends her evenings helping at Grisham Middle School.

Van Bui is next to arrive, the clock reading 10 a.m. as he straightens the hat on his head. Emblazoned with the word ‘WOLF,’ the cap speaks differently to his quiet demeanor.

“I’m just here to do my job,” Bui said. “When I’m working, I’m working hard.”

Full employee benefits and a quick turnaround from application to hiring are considerable offsets to low pay.

“This is the first time I’ve been to this kind of job in my life,” Bui said. “I’ve been retired, but I came here looking for some work to have income coming in.”

Having worked in systems analysis nearly 40 years prior, Bui’s employment history across fields is robust in its diversity. A testament to the core of the immigrant experience, a layered resume builds upon transferable, all-encompassing skills.

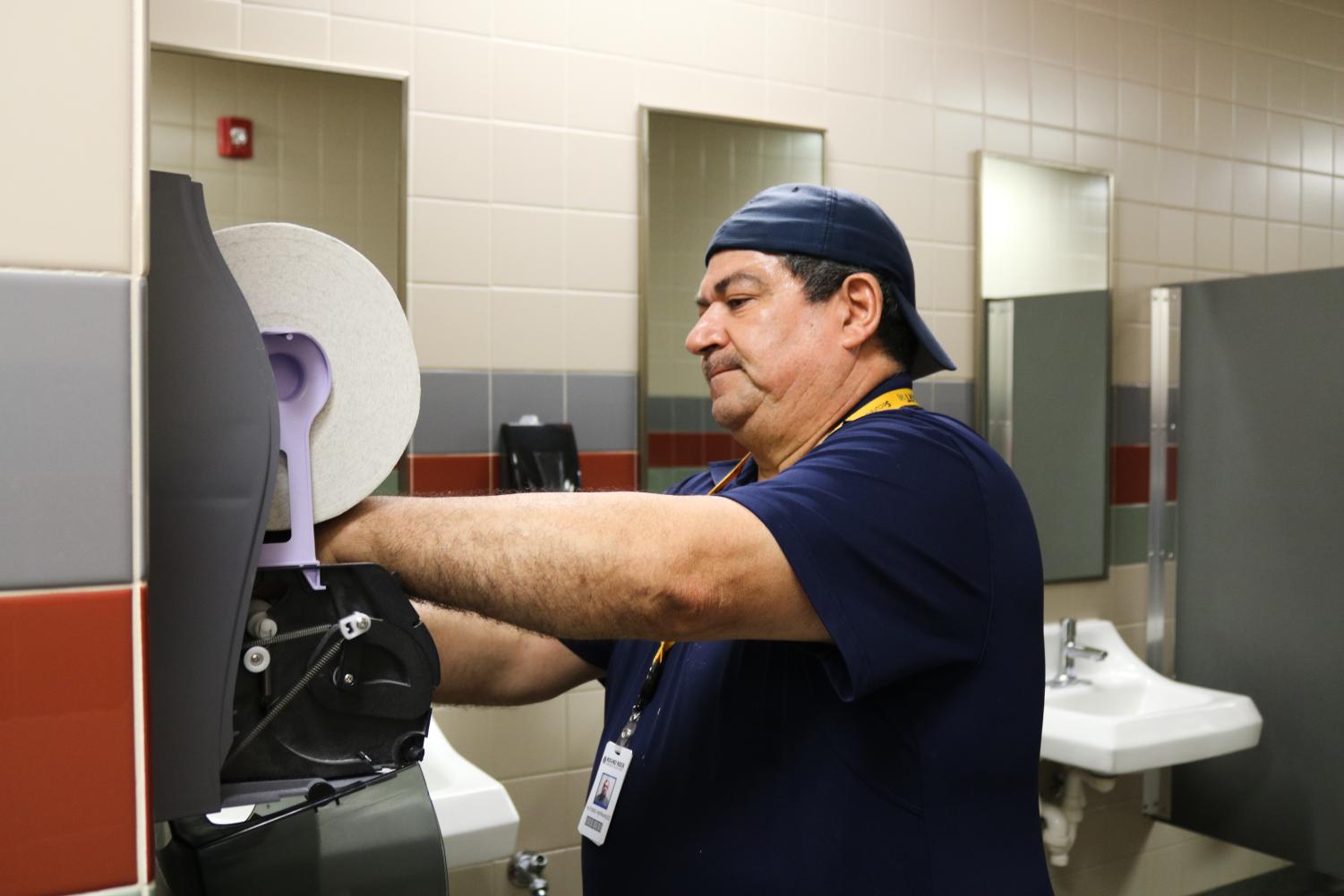

Once lights flicker, or doors skew, the same custodians who ensure cleanliness of school facilities are called to the scene.

For Bui, experiences culminate across spheres of work and life.

“My life now, the thing I am happiest [about] [is that] all of my children are well-educated,” Bui said. “That’s what I’ve been praying for. And now, [I have made] it. They’re on their own.”

This is what Bui ponders on from his post at the back of the cafeteria, waiting to wipe down tables peppered in crumbs and trash.

Weaving through the sights and sounds of post-lunch clamor, Maria Gonzalez picks up her responsibilities at noon.

“For me, everything is easy,” Gonzalez said. “Difficult, never. I can always work it all.”

While custodians develop the same spatial connection that students build with classrooms, the size of Westwood however, does not shrink with familiarity.

Assigned to distinct areas of the school, custodians exercise a certain degree of ownership for these locations, a responsibility that defines the commitment to their job.

“People don’t realize that [for] the district custodians, their campus is their second home,” RRISD Custodial Director Ruben Dominguez said. “If that school is dirty, that means their house is dirty. They have this pride in making sure our campuses are clean.”

Afternoons prove quieter, facilitating some of the only moments of tranquility where the day-time custodial team can fit in a late lunch.

Tamale spices permeate the hallways, their fragrance perfuming Gonzalez’s bright laugh from the receiving room, which also doubles as a rest area for the custodial staff.

As the daytime crew heads out at 3:30, Pedro Minan sets on the 20-minute walk from his home to the school. Without a car, his job options are limited—proximity the only condition tethering him to this position.

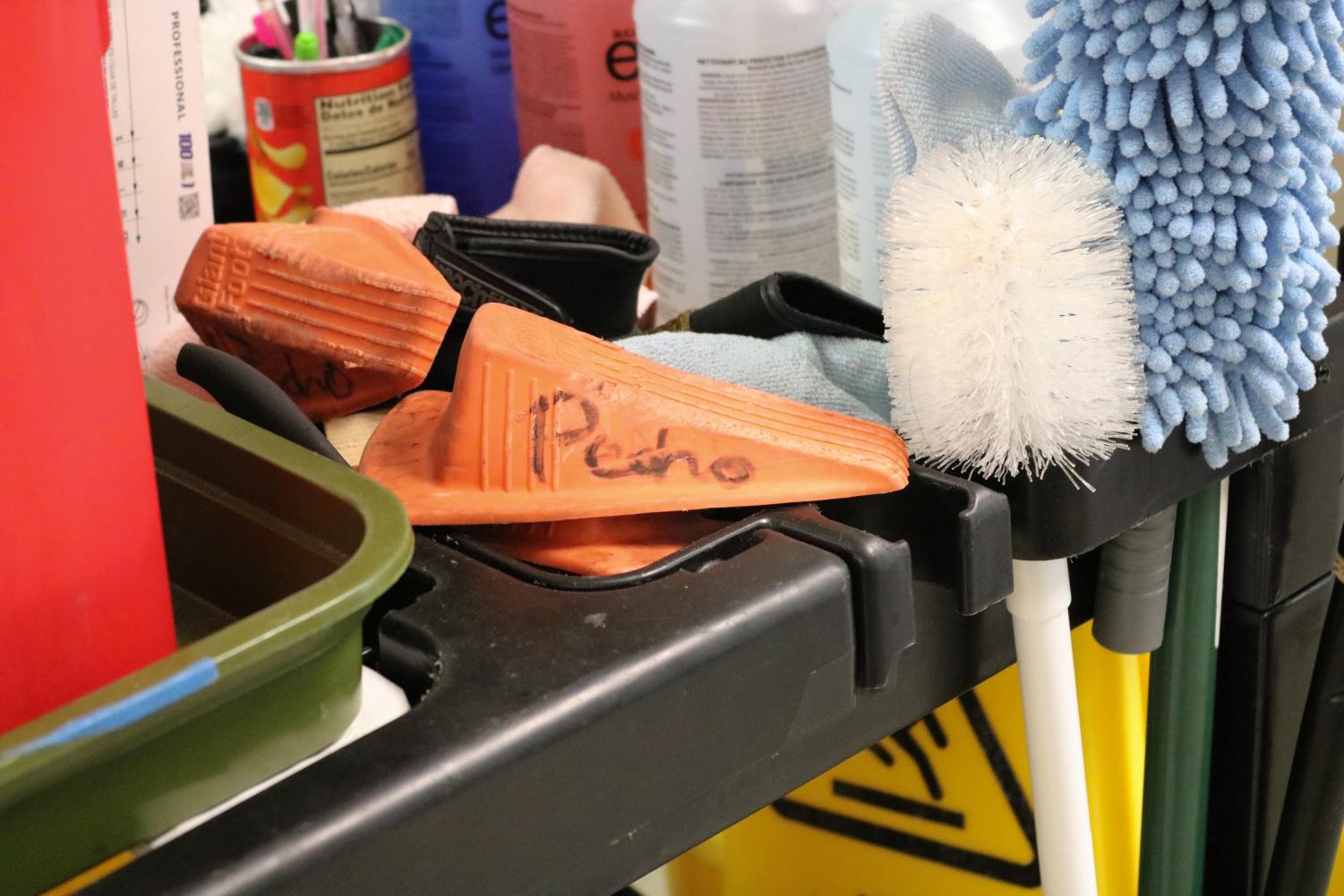

Brooms and various other tools jut out from a weathered yellow cart parked outside of E1308A, the furthest end of the downstairs E-Wing.

Minan’s realm descends from the stairs, to the windows, bathrooms, and finally classrooms, every stop scrawled in a timesheet. Pages blotched with disinfecting solution hold records of extra areas he covers.

“How [the rest of the custodians] feel is how I feel,” Minan said. “All of us are practically united. In reality, the job is very hard here, and there are times that I will do double the work.”

Reaching for the rubber stop he leaves wedged between doors, Minan’s attention to detail is reflected in the tangible items that enable him to execute each task with precision and individuality.

“Here, everything is work,” Minan said. “I listen to my music, and with that I relax.”

Amplifying sentiments no less true for his co-workers, Minan employs a steady mindset to overcome challenges tied to labor-intensive and repetitive work.

“My health does not affect me yet,” Minan said. “But here, I see that there are several people who are affected by their neck. The moment will arrive in which my time will come. For your body it is so. It gradually wears out.”

Up the stairwell, Alfonso Hernandez straightens bottles of Oxivir disinfectant adjacent to bible verses that many custodians also look to. When district support is minimal, the connection amongst themselves stands out.

“Someone always has to do [the] work,” Hernandez said. “Most of the work we [as custodians] do. Who else? I don’t have to say who, but you know. Immigrants. So, what happens is not [a sense of] unity [between the custodians]. It is necessity.”

Most of the work we [as custodians] do. Who else? I don’t have to say who, but you know. Immigrants. So, what happens is not [a sense of] unity [between the custodians]. It is necessity.

— Alfonso Hernandez

For a school as involved as Westwood, seeing beyond the rhythm of academics and activities requires conscious consideration for the people who take care of the spaces they occur in.

“It’s a school. Students should have a little more respect for their own campus,” night custodian Jose Jaimes said.

Once after-school activities come to a lull, and the last students leave for the day, the custodial team is left to reset for the next.

“At bigger schools it’s hard, because [some custodians] come in so much later that students have already gone,” Dominguez said. “Not a lot of students see our custodians at night.”

What transcends the monotonous nature of the job is a call to community.

“[I] only [wish] that I serve the school; for the students and teachers,” night custodian Filiberto Velazquez said.

Class of 2023

Ardent advocate of em dashes, pastel cardigans, and above all, the written word. Amoli and I are honored to lead a publication by students,...

![Westwood students experienced the impacts of class cuts resulting from Round Rock ISD (RRISD)s budget deficit. The recently approved general fund budget could have played a role in returning some of the cut classes. We all hope that [the general fund budget] will bring additional funding and cost savings, potentially help with course and extracurricular operations, and provide deserving teachers with an increase in salary as well as provide better education opportunities for students, Marlene Luo 25 said.](https://westwoodhorizon.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ww-pic-600x479.jpg)