Gathering for their most complex dissection of the year so far, Anatomy & Dissection Club members met in Mr. Eric Scheiber’s room on Friday, Jan. 17 to explore the internal intricacies of the blue crab. The crab’s exoskeleton distinguished it from the vertebrate organisms the club had dissected earlier in the year.

“It’s interesting to take an organism like a crab that has that calcified structure and is more soft [and] easier in size to get through [than] other organisms,” Mr. Scheiber said. “They’re also marine, and we don’t do a lot of marine organisms in [Anatomy & Dissection Club].”

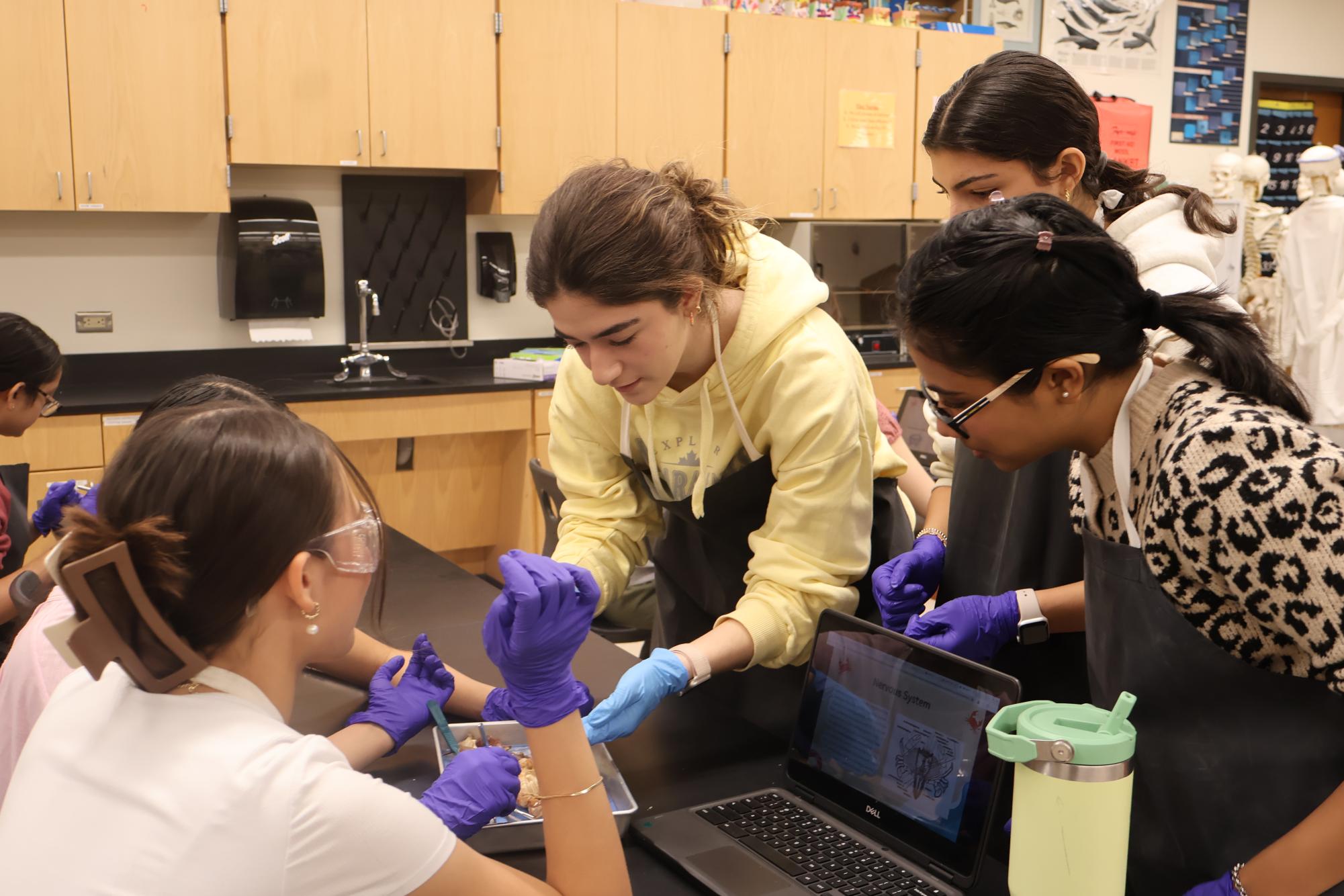

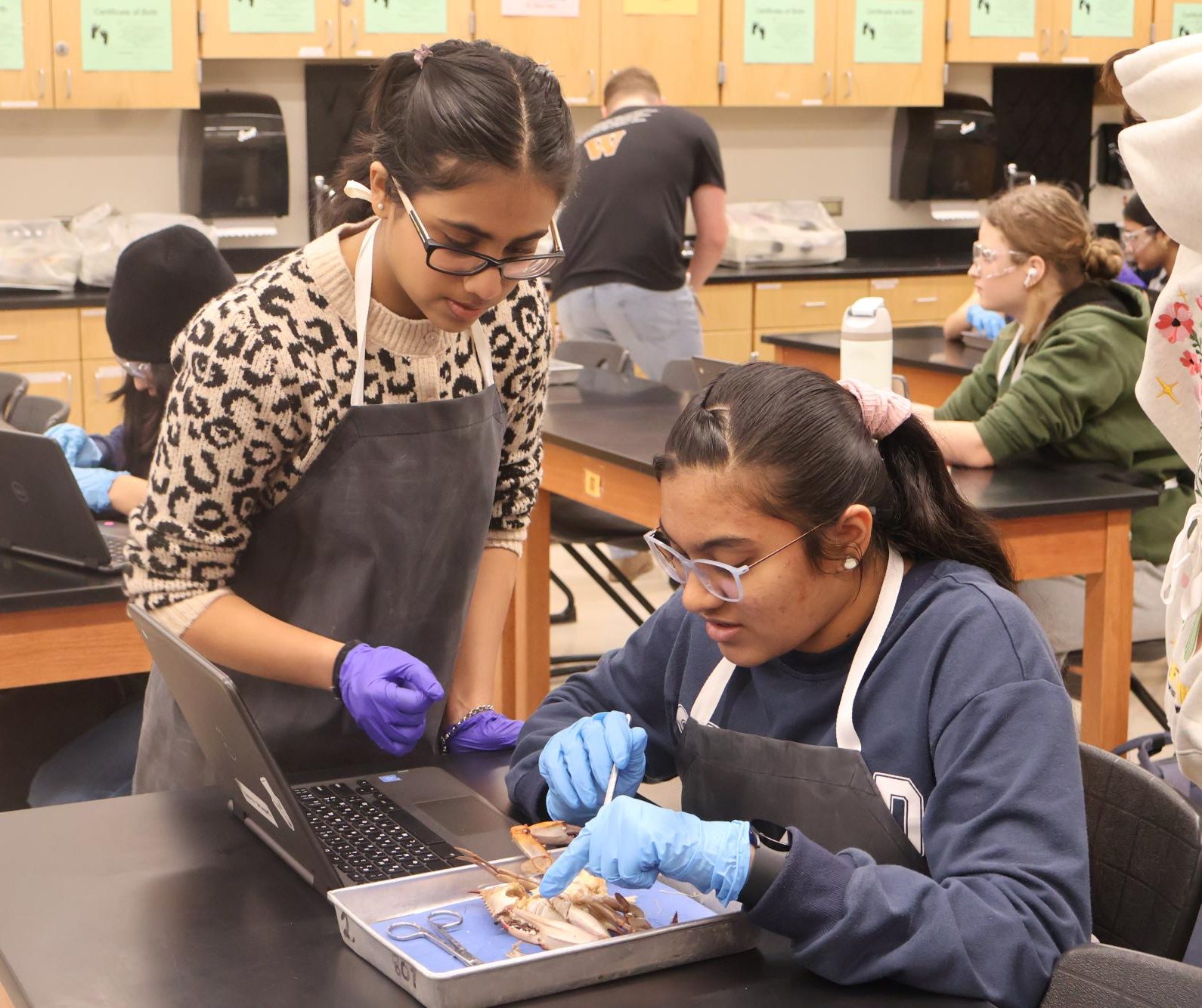

For many participants, the hardest step was taking off the crab’s shell, which resisted the scalpels at first. The students used a combination of scalpels, scissors, forceps, and their own gloved fingers to pry the crab open. Some of them struggled to get into the crab without damaging its insides, especially if they used the scissors or forceps to bludgeon the shell.

“The shell was really hard, so it was tough to get into,” Anatomy & Dissection Club Treasurer Ava Poursepanj ‘26 said. “We used a scalpel to cut in the middle and open it up.”

After instructing members to remove some protective plates over the crab’s abdomen, the slides provided by club officers detailed how to pull out components of the crab’s digestive system to expose its nervous system. Some of the dissection participants were surprised by what they observed of the crab’s internal organs.

“Crabs don’t have veins or blood vessels, so it’s kind of weird, seeing all the organs just there and just open like that,” Gabriel Oliveira ‘26 said. “It was very thought-provoking, because when we opened the crab, it still had chyme — the food that the crab hadn’t fully digested yet — and that really made you think about what the crab went through and how that led to it being on our dissection tray.”

Another one of the challenges that participants encountered when attempting to identify the crab’s internal organs was the high quantity of extraneous tissue everywhere in the crab’s body. Only some of the students were able to identify the heart and brain amid the yellow, soup-like chyme that emerged when the stomach was ruptured. The rest of the crab’s elaborate anatomy also proved difficult to identify and comprehend.

“I was expecting a visible heart, or maybe a brain or something,” Oliveira said. “But it [all] seemed like it was so alien, and the organs had different functions than what is present in humans or other animals, or even in fish or reptiles.”

Because unfamiliar anatomy complicated the process, the officers walked around to assist the other students and shared fun facts about the crab’s lifespan, leg functions, and molting processes.

“[Crabs] develop from eggs that are laid, and not many of them survive, because so many eggs are laid at once,” Scheiber said. “So, the ones that actually make it to the ocean and grow up and live and thrive [are] lucky for that species. There [are] many different species of crabs that do huge migrations on islands, from beaches to mountain tops, in order to find their mates. They have special, interesting behaviors. So it was very nice that the officers wanted to include this organism.”

The club members left the dissection with new skills — such as how to identify the sex of the crab, and new knowledge — including the fact that crabs breathe using gills.

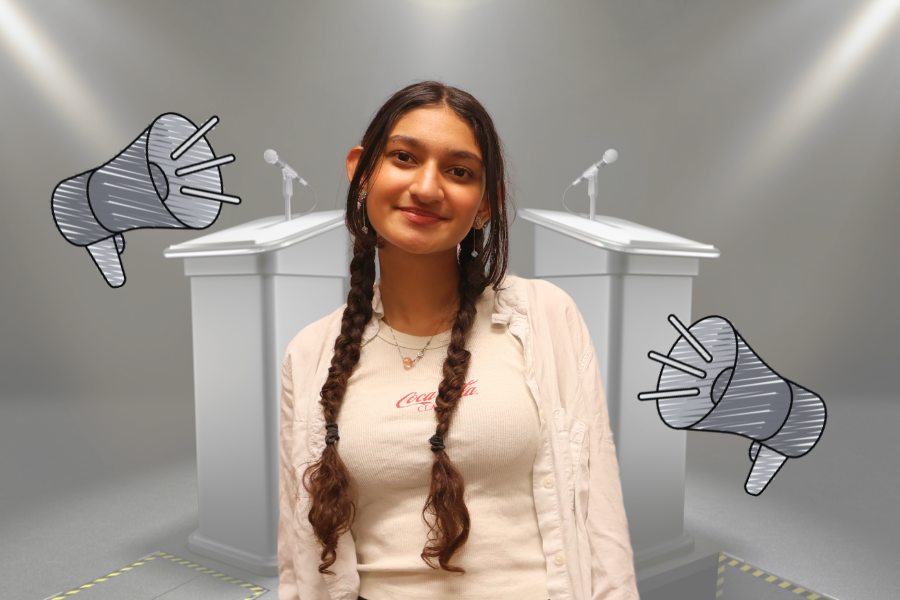

“I thought the gills were a fan favorite, because you can actually tell where the layers are, and if you squeeze [them], the water comes out,” Anatomy & Dissection Club Secretary Niranjana Prem ‘25 said. “I thought that was cool [and] memorable.”

Anatomy & Dissection Club will host their next meeting to dissect pigeons on Friday, Feb. 21.