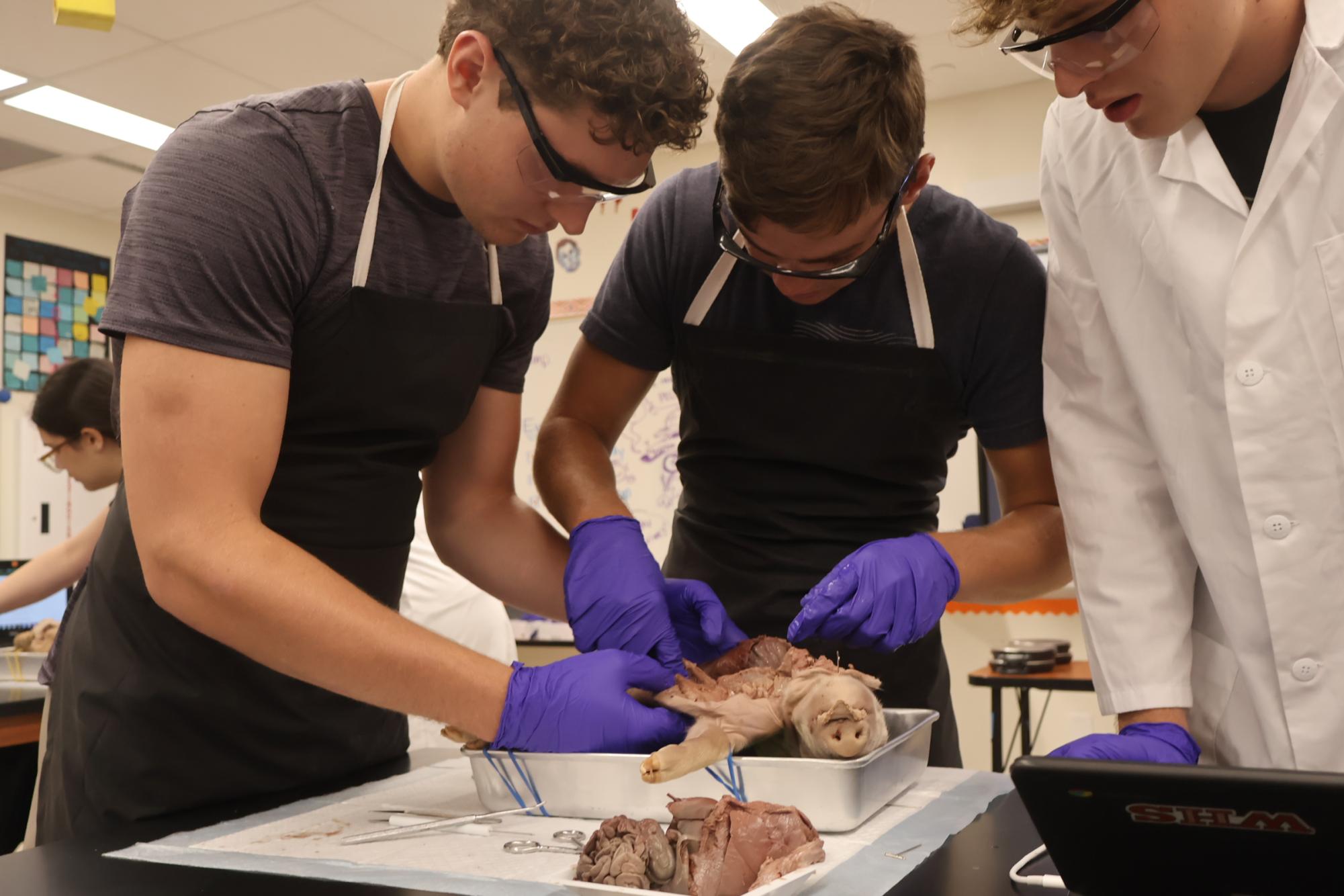

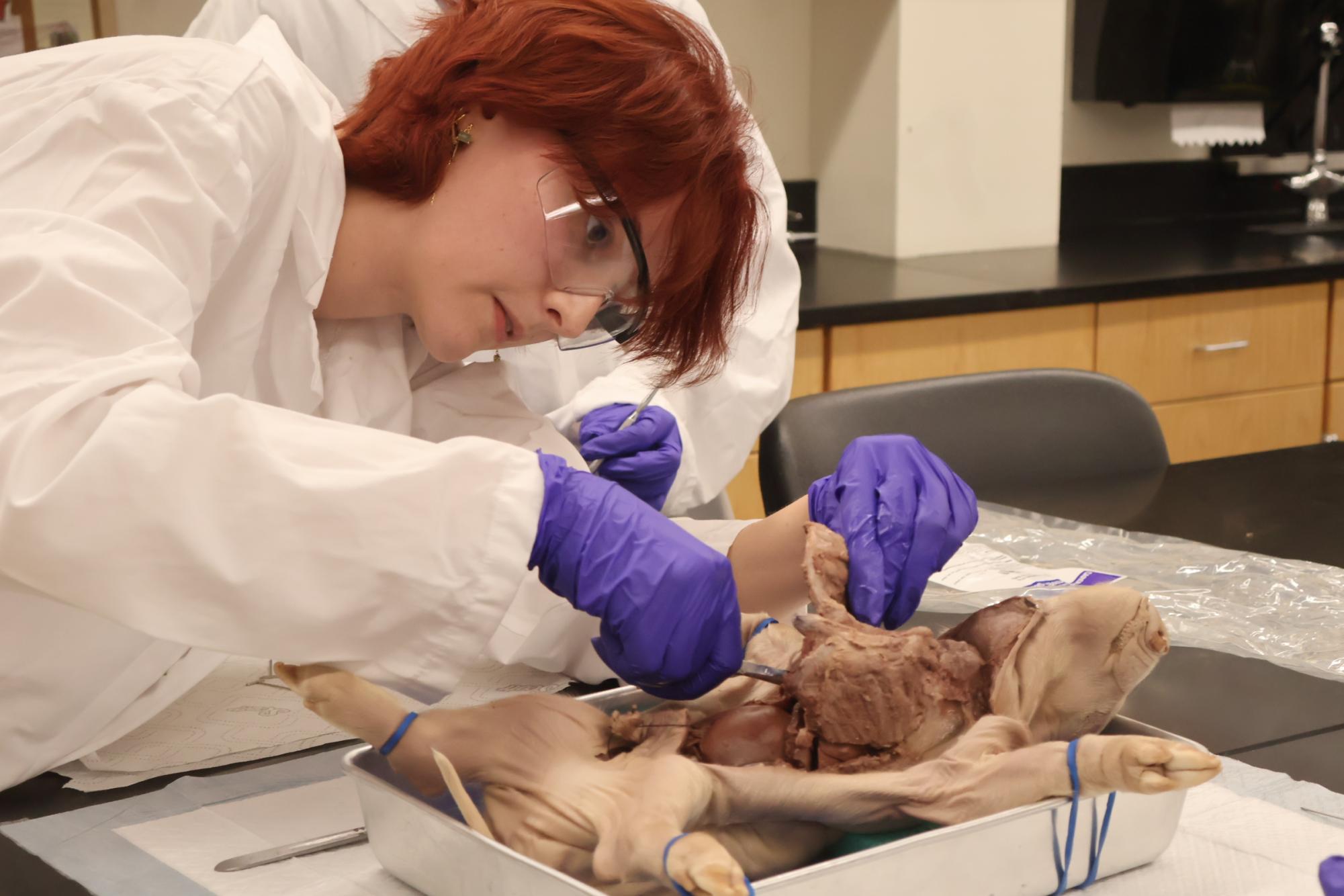

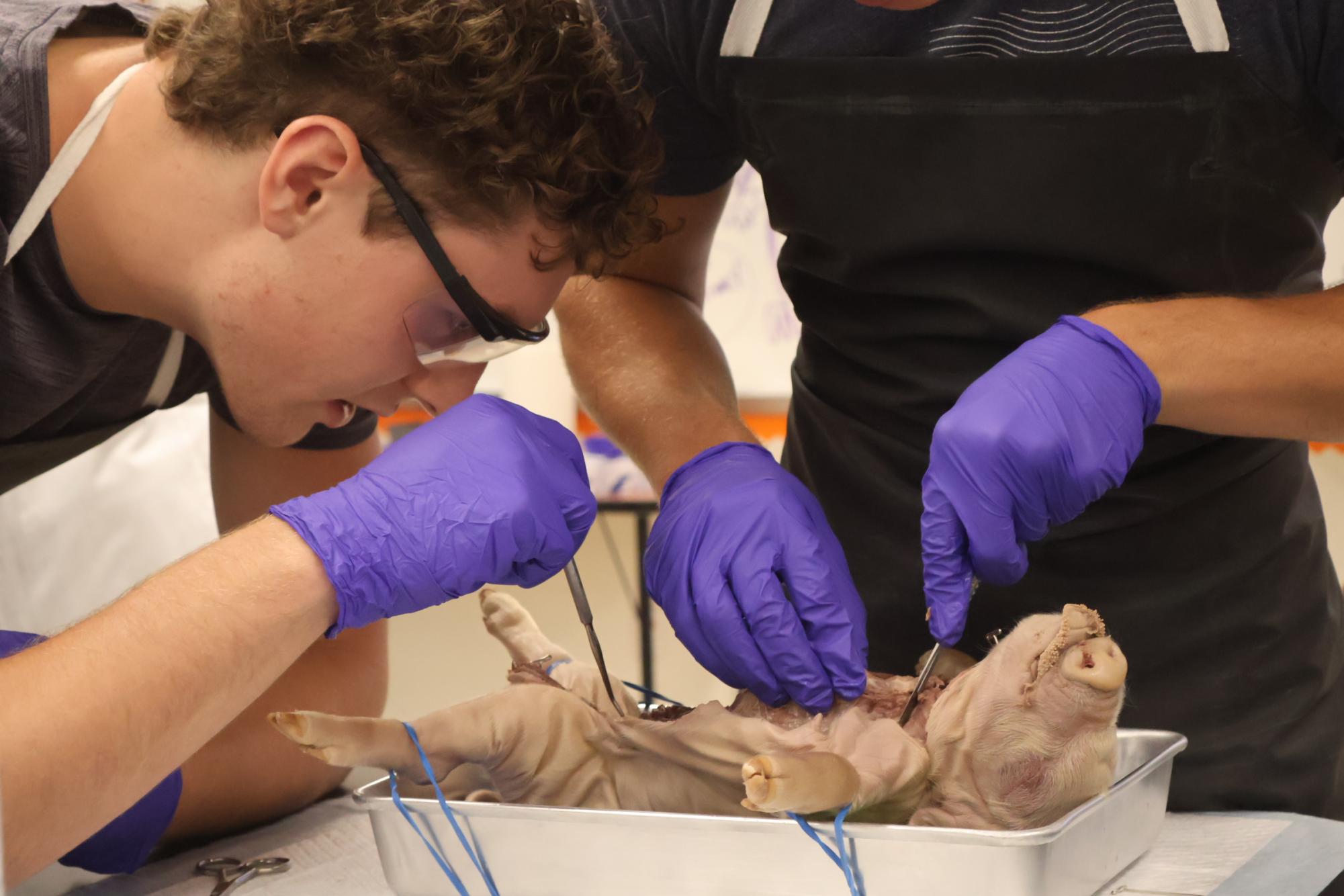

A macabre conclusion to their unit on death and decomposition, forensics students took on the roles of forensic pathologists to perform medico-legal autopsies on fetal pigs. The process, during which students attempted to determine the “manner, cause, and mechanism of death” for the pigs, took place over the course of five blocks and ended on Friday, April 11.

“It’s a unique opportunity for students to dissect a mammal instead of a frog or starfish. [Pigs are] a little more humanesque,” Forensics teacher Ms. Shawn Sieber said. “Basic understanding of their body is key. [The dissection gives students] an idea of what they might actually be interested in in the future, but also what they can handle realistically.”

An alternative to the ethically questionable use of human cadavers, fetal pigs are a common dissection due to similarities with human anatomy. Using fetal pigs also provided students with the opportunity to interact with an organism that is not dissected in other classes to keep the experience new and exciting.

“Pigs are weirdly similar, anatomically and physiologically, to humans, and so because we’re doing an autopsy, it’s really important to have an animal that mimics the human body as closely as possible,” Ms. Sieber said. “I wanted my students to go through the real process of an autopsy, step by step, organ by organ, structure by structure, and pigs are always the best option for that.”

With many of the students planning to pursue a career in medicine, the autopsy was a glimpse into some real-world medical and forensic tasks.

“Every year, I have students who are like, ‘I’m going to be a doctor,’” Ms. Sieber said. “This is a really good indicator of if you’re actually equipped to be a doctor or a nurse or something in healthcare. It’s better to learn that now than to learn that when you’re halfway through med school, so I like to give experiences that help students understand their skill level and their comfort level.”

The district carefully obtained the pigs from specific vendors who ethically source and correctly preserve their specimens. The process requires registering with the companies and getting approval from the Career and Technical Education (CTE) department by demonstrating the importance of the autopsy and how it aligns with the class.

“[The pig dissection is] definitely a long process, but we’ve done it for almost six years at this point, and it’s one of our favorite labs that we do all year long,” Ms. Sieber said. “All I know is that any kind of dissection specimen is [under] really strict guidance and it’s not just the district — this is a federal-level thing.”

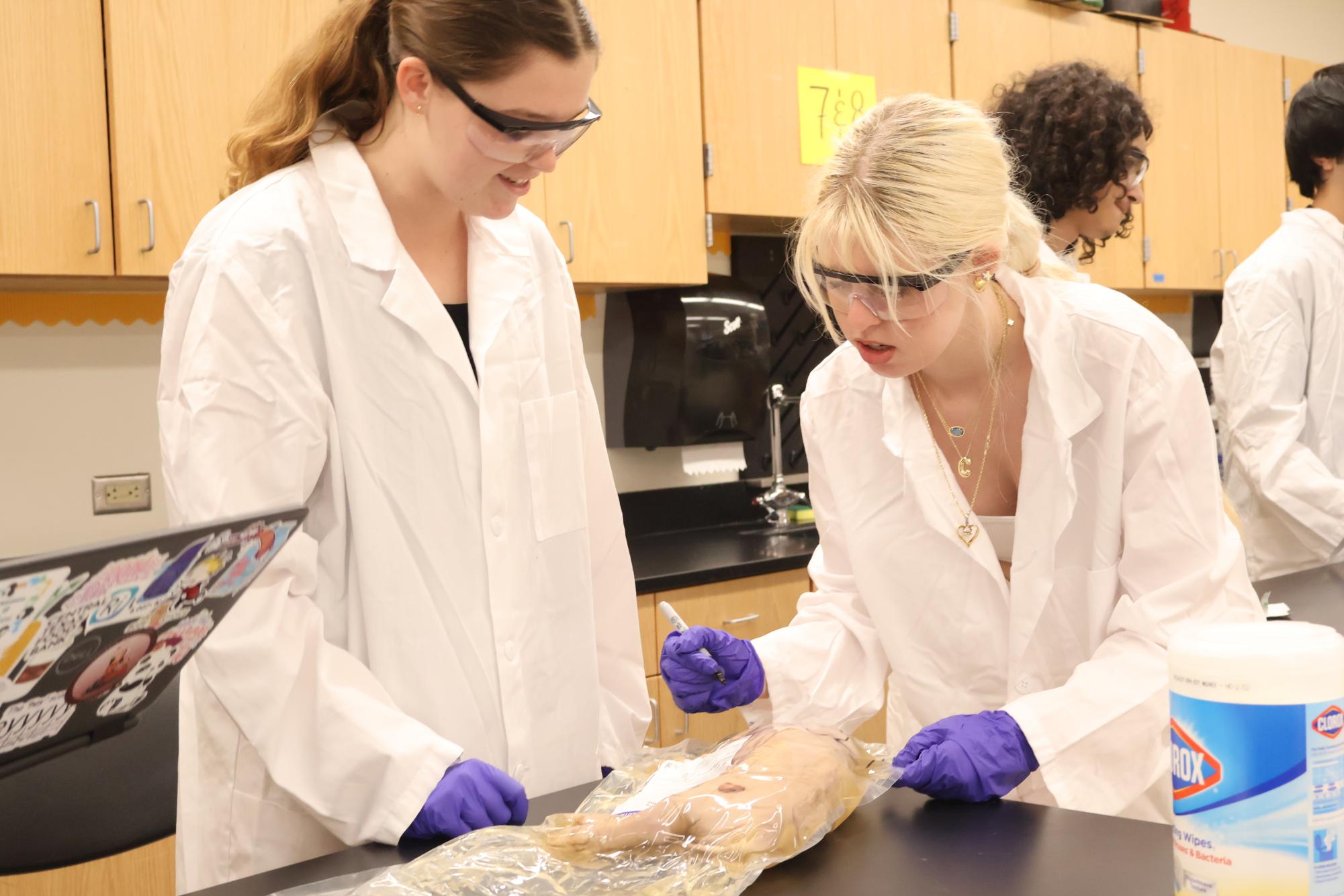

Before the autopsy, participants were split into roles based on their comfort level, with the most enthusiastic students serving as their group’s prosector, or dissection lead. They also read over their protocols and named their pigs.

“We learned about all the tools and all the parts of the pig because we’re trying to go through an autopsy, so we learned about all the steps before,” Indy McBrearty ‘25 said. “We called our pig ‘Harriet’ because of its hair.”

Seeing the pig for the first time came as a shock to some students, who had to adapt to the situation.

“I was a little nervous,” Delaney Johnson ‘26 said. “It was just a dead pig on the table. But as you go into it, it gets less nerve-wracking, because you see it more as an experiment than as a pig.”

On the first day of the procedure, the students took measurements to estimate an age, which led into their external examination of the pigs’ dorsal and ventral features. Afterward, they secured their pigs to the trays using a body block and rubber bands. This prepared them to make a Y incision, exposing the pigs’ internal structures for observation.

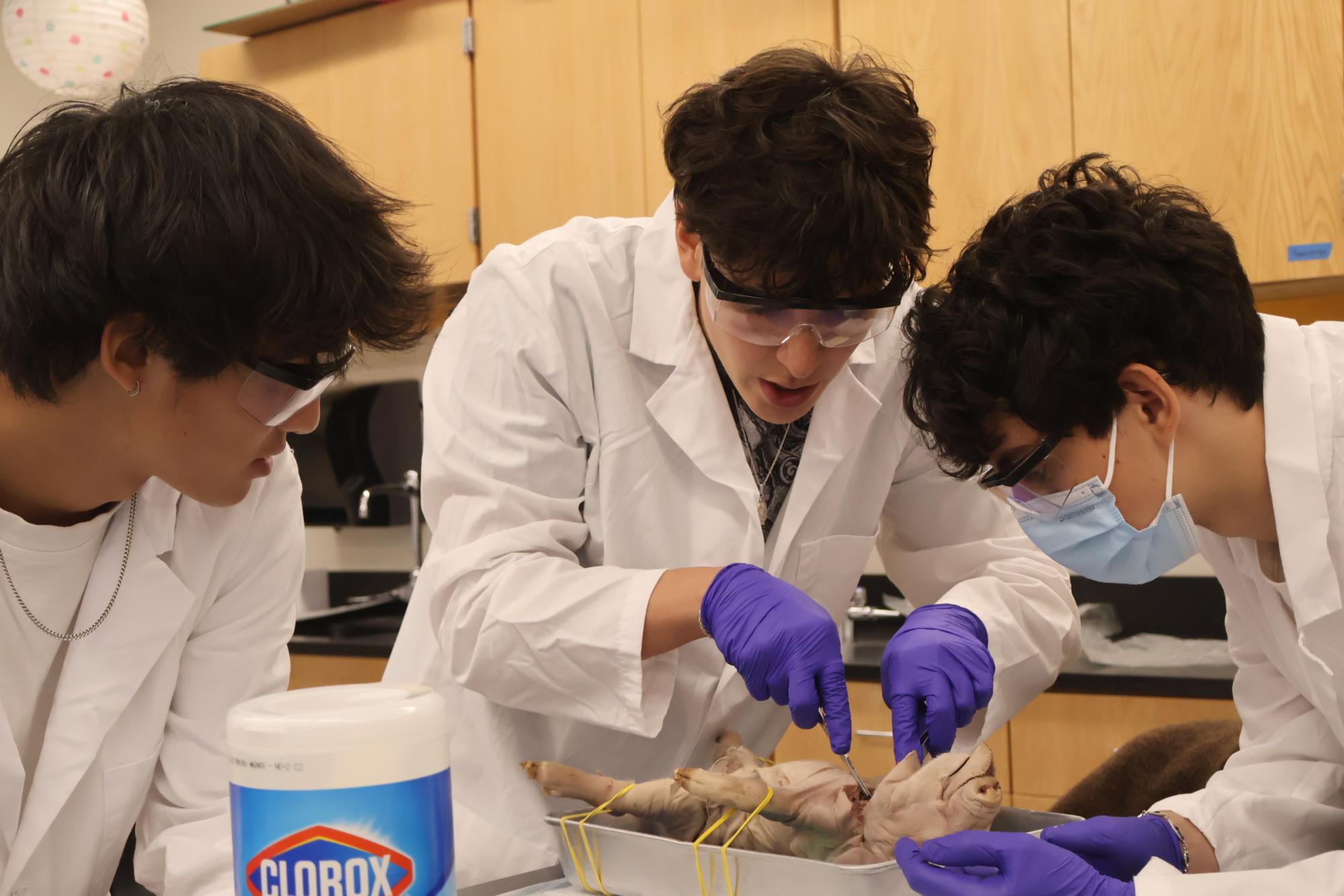

“I think the first cut was kind of challenging, because we didn’t want to cut into it,” Cody Propes ‘25 said. “Cutting open the heart was pretty fun. We could see all the blood that clotted, and we could see all the arteries and the veins poking out. [We concluded] that there was internal bleeding somewhere. I learned that there’s a lot more juices and guts and blood than I thought would be in a pig that small.”

Next, the students slid their fingers under the pigs’ organ blocks and cut away to remove the long, connected system in one unit.

“You have to be willing to get your hands dirty,” Ishira Limaye ‘25 said. “You have to put your hand in the body cavity and pull out the organs, so the mental part [was challenging].”

Throughout their observation, the students looked for signs of disease or trauma to form conclusions. They examined organs such as the lungs, heart, liver, and stomach for potential causes of death. Although the pigs were never born, pieces of evidence such as bubbles in the lungs or clotting in the heart suggested plausible situations if they had died.

“A lot of the organs are black or gray when they’re supposed to be peach-colored, so that’s a sign that there’s drugs in the bloodstream and then there’s also a lot of internal bleeding, which can be caused by poison,” Johnson said. “I think the most interesting moment was when we cut out the organ block, because all of the organs stayed together — you could just place it back in the body perfectly, but you can also take them out and they just stay together and that’s kind of cool.”

In order to block out the strong smell of the specimens, most of the people in the room wore masks and smeared scented ointment under their noses. The doors were also opened to help with ventilation, flooding the hallway with the aroma of formaldehyde.

“The smell was pretty bad,” Rahul Kuthiala ‘25 said. “It was just really graphic. It was just a dead body, and a lot of people haven’t seen that before.”

To conclude the procedure, the students placed the organs back in and sutured the incision closed. To advise the students on how to use the needles correctly and help them through obstacles, surgeon Dr. Cara Govednik visited during 3rd block on Thursday, April 10 and walked around to help.

“I am a physician, and I do a lot of suturing, so I was asked to come help out,” Dr. Govednik said. “You use [suturing] for every surgery. You make an incision, so you have to close that incision, and if [you’re] doing autopsies, then [you] need to close the patient afterward. [I was teaching] some of the basic suturing techniques, different types of sutures that we use — continuous versus interrupted — and how to hold the instruments.”

The autopsy supplemented students’ learning by providing them with a hands-on dissection experience with cutting open a specimen and making scientific inferences about the circumstances of its death.

“Our pig specifically has a very large heart, and there’s discoloration on the liver and the kidneys, so that was kind of cool,” Limaye said. “You can actually see when things are abnormal. And it was also really cool to see all the different organs because you’re constantly learning about, ‘Oh, your lungs do this, your ribs look like this, your liver looks like this,’ but to actually see it in a mammal is really interesting.”

![Holding her plate, Luciana Lleverino '26 steadies her food as Sahana Sakthivelmoorthy '26 helps pour cheetos into Lleverino's plate. Lleverino was elected incoming Webmaster and Sakthivelmoorthy rose to the President position. "[Bailey and Sahiti] do so much work that we don’t even know behind the scenes," Sakthivelmoorthy said. "There’s just so much work that goes into being president that I didn’t know about, so I got to learn those hacks and tricks."](https://westwoodhorizon.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/IMG_0063-1200x1049.jpg)