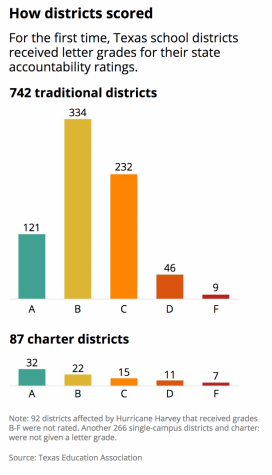

Texas School Districts Receive Official A-F Grades

Look up how your district did here.

Texas gave its school districts their first official grades Wednesday, fueling the fire of a years-long political debate over whether an A-F rating system will help parents determine the best options for their children.

State officials argue that the new grading system for school districts is more transparent than ever, especially when compared to the outgoing pass/fail rating system. The Texas Education Agency also created a website that will eventually allow parents to look up their districts and schools and immediately see a letter grade as well as peruse the many data points and calculations behind it.

“There’s some level of understanding about what A-F means, and that’s part of the reason of what makes this easy for families,” said Penny Schwinn, TEA deputy commissioner, at a briefing for business and legislative officials Tuesday.

Former Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams, who had Texas rolling toward an A-F rating system in 2013, released a statement Tuesday saying the ratings would “kickstart the conversation around school quality.” Williams is now the board chairman of Texas Aspires, an advocacy group in favor of stricter accountability measures for students and schools.

School superintendents and educator advocates vehemently disagree. They argue state officials are stuffing numerous important metrics into a single, simplified letter grade, ultimately misleading parents about how a single school or district will serve their children. Since last year, more than 50 school districts are organizing to create their own “community-based accountability” systems, which include measures beyond state standardized test scores, such as parent survey results and the availability of student clubs.

“This system is designed to make parents angry at schools and districts when their fury should be directed at elected and appointed officials who pushed this system designed to shame public education,” reads a release from Texans Advocating for Meaningful Student Assessment, which opposes high-stakes standardized tests.

Since Florida became the first state to adopt an A-F accountability system in 1999, several other states have followed suit — sparking similar debates about whether a graded system is clear for parents or fair to schools. Each state calculates its grades in different ways.

Texas has gone through multiple rounds of retooling its calculations across two legislative sessions. During the most recent session in 2017, lawmakers decided on a rating system with three categories: student achievement, school progress, and closing the gaps.

School districts receive a letter grade for each category to reflect how well their students perform on the state standardized tests and whether they are ready for college and careers (student achievement); how much students are improving on state tests (school progress); and how well schools are boosting scores for subgroups such as students with special needs and English language learners (closing the gaps). They also receive an overall grade.

The calculation behind the overall grade is complicated: 70 percent is based on the “student achievement” and “school progress” categories, with the state only counting the better score of the two categories. The “closing the gaps” category makes up the other 30 percent.

Schools will not receive official grades until August 2019, a compromise lawmakers made last spring to appease critics of the new system. But the state Wednesday did release numeric scores for schools, which can be easily translated to grades.

The rating system’s heavy reliance on state test scores as a measure of student performance has angered educators, who want less overall emphasis on those tests.

But the state argues that standardized tests, which are tailored to the Texas curriculum standards, offer one of the only consistent statewide metrics and must be included. Currently, 10 school districts are piloting locally developed rating systems, allowing them to choose additional performance measures such as extracurricular participation.

“We can’t actually create a system that holds the expectations that we all have for our individual students, because all of our students look different, come with different knowledge bases, skill sets, etc,” Schwinn said Tuesday. “It is de facto imperfect.”

This story is from The Texas Tribune. The Texas Tribune is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.