Travel Restrictions to Stop the Spread of Coronavirus Will Backfire

Opinion

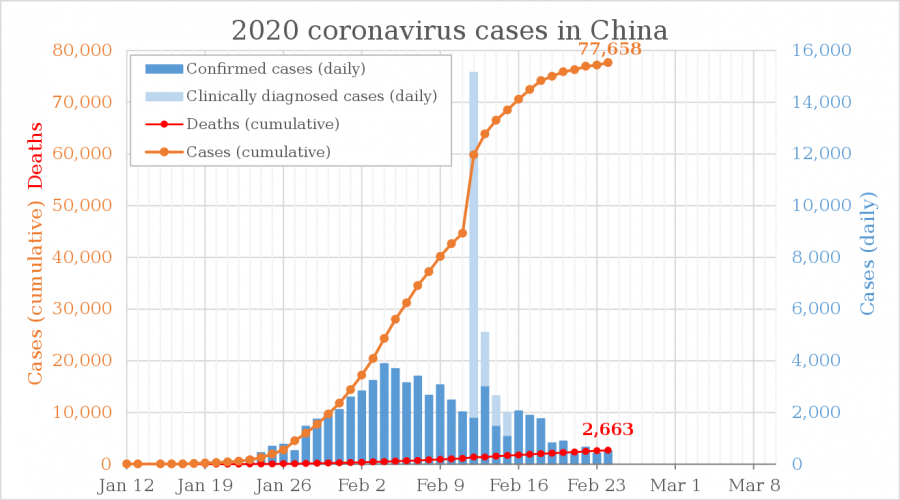

Since its first diagnosis last December, the coronavirus, now officially named COVID-19, has continued to spread around the world. Around 80,000 people are confirmed to be infected with the disease, and over 2,000 have died, although many were already in poor health before they experienced the symptoms of COVID-19. Outside of China, where the disease was first detected, more than 47 other countries have confirmed cases of the virus. The U.S. is one of these nations, with 60 confirmed cases as of Feb. 27. Recognizing the concerning expansion of the disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency on Jan. 30 for the outbreak.

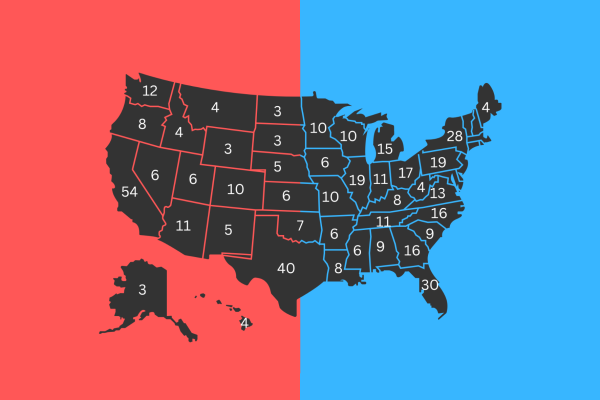

With new developments emerging seemingly every day, confusion, worry, rumors, and hysteria are growing. On a bureaucratic level, news of the coronavirus has received the alarm of dozens of countries, cities, and businesses all over the world. These organizations, fueled by fears of the disease spreading further, have issued warnings and imposed bans to try and stave off the virus. On Feb. 2, the United States joined them, brandishing new restrictions around travel to and from China. The administration is mandating Americans who have recently been in China’s Hubei Province, where the disease was uncovered, to be held in quarantine for up to two weeks. Citizens who visited other parts of mainland China are being forced to undergo screening and two weeks of monitored self-quarantine. Foreigners, on the other hand, are completely barred from the country if they visited China in the past few weeks.

Since the U.S. took action against the coronavirus, other countries have predictably followed in its footsteps. Australia and Japan have begun denying entry for Chinese nationals. At the same time, Iraq has barred people who have visited China and Italy has even warned that it will prevent all Chinese people from entering.

Though a travel ban seems like the perfect way to confine the disease to one area until a cure is discovered, it has more potential to harm the public than help. Throughout history, governments have attempted to seal their borders whenever threats of a pandemic arose. During the SARS epidemic in 2003, which has been likened to the current coronavirus outbreak, cities shut down travel and necessitated screenings of people at their borders for the disease. When an Ebola outbreak threatened the world from 2014 to 2016, many states instituted quarantines, while the Obama administration forced travelers from West Africa to fly into the U.S. through airports with screening procedures implemented.

However, as the evidence from past experiences like these demonstrate, restrictions fail to truly stop the spread of diseases. In the cases of bird flu, swine flu, and many other epidemics, travel limits only led to slight delays in the outbreak’s reach at best. Realistically, it’s almost impossible to completely close a country’s borders, because people can inevitably move from country to country. When the SARS outbreak reached Canada, the government quarantined thousands and screened millions at airports, but didn’t find a single case of the disease. Now, this situation is reflected in the coronavirus, which can be spread before symptoms are shown and was likely carried by civilians traveling with little to no symptoms before the epidemic was even realized.

The bans don’t delay the disease’s spread significantly, but they do delay progress in curing it.

The bans don’t delay the disease’s spread significantly, but they do delay progress in curing it. Travel restrictions use up countries’ resources and funds, sabotage collaboration and information sharing to track the disease, cut off the medical supply chain, and hurt the economies and businesses in affected locations. In trying to keep the people safe, governments actually worsen their suffering by holding the international community back from finding a proper solution.

Already, experts have warned that restrictions such as the ones the U.S. has placed against the coronavirus will backfire. “Doing things out of an ‘abundance of caution’ isn’t a good idea,” Tara Sell, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Preparedness, said. “The risks [and] costs of the travel ban and some of the severe quarantines that we are seeing around the world, those have real consequences.” Adam Kamradt-Scott, a professor in global health at the University of Sydney, confirmed that these types of measures “have been shown to be ineffective at halting the spread of the viruses.”

Already, countless Asians around the world are feeling more and more alienated by other people as a result of these fears.

That’s not where the story ends. Travel restrictions have another consequence that manifests in the countries applying them. As WHO Chief Tedros Ghebreyesus stated, widespread travel bans and restrictions “have the effect of increasing fear and stigma.” As countries implement these measures, stereotypes and assumptions will begin to form that Chinese people or Asians in general are more likely to carry the coronavirus. Many past outbreaks, such as the Zika virus epidemic in 2015, exemplify this trend, but also show that this “ethnic scapegoating” is distracting and unproductive.

Already, countless Asians around the world are feeling more and more alienated by other people as a result of these fears. When Rosen Huynh from California criticized her professor for telling students who had recently traveled to China to stop attending class, she received abundant racial slurs and hateful replies targeted at her East Asian roots. Others have relayed their own stories on social media of being verbally and physically abused, blamed for creating the coronavirus, refused service at stores and restaurants, and watched strangely or avoided in public.

Ultimately, travel restrictions not only fail to contain the outbreak but also hurt the international community’s ability to fight it and amplify xenophobic attitudes against people who don’t deserve the blame. Aside from the obvious immorality of racism, there are health-related consequences to discrimination as well. For example, people who face prejudice may be less likely to get medical treatment for their symptoms because the restrictions appear to criminalize the disease and threaten those who have it.

If not placing travel bans, then, what should countries be doing to combat the coronavirus? As experts have noted, there are several other measures proven to be much more effective against diseases. Providing assistance to countries with weaker health systems, focusing resources on accelerating the development of vaccines and medical research, and maintaining transparency with the public on how to seek care are all valid examples of how governments can act against the epidemic without causing more unneeded fear.

When disease threatens global society, unwarranted xenophobia is not the answer.

Meanwhile, instead of buying face masks or avoiding every Chinese person around you, the CDC recommends that the best way to keep yourself healthy is to stick to the typical methods of avoiding viruses: staying home if you’re sick, covering your nose and mouth when sneezing, regularly disinfecting objects that could be contaminated, and regularly washing your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. Be cautious, but don’t panic.

Facilitating a rise in racism with travel restrictions only hinders the world from finding a solution more efficiently. When disease threatens global society, unwarranted xenophobia is not the answer. “Treat people who exhibit symptoms rather than targeting people for quarantine or barring them from public places simply because of the way that they look,” Erika Lee, professor at the University of Minnesota said. “It’s really about using common sense and not letting fear and panic drive us to revert back to more base fear of foreigners.”

This is my second year on the student press staff and first year as an opinion editor. Aside from writing stories and taking photos for press, I spend...