The Structure of AP & IB Curricula Needs to Change

May 19, 2023

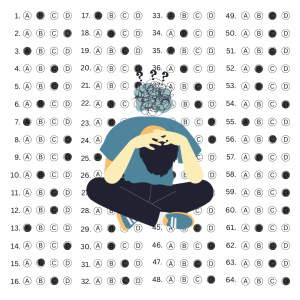

As stress levels culminate and testing anxiety permeates the halls, it is a clear sign that it is testing season. Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB) testing occurs during the month of May, and they allow students to receive college credits from their classes if they obtain a certain score. Despite the preparation and college readiness that these programs aim to bestow on their students, the exams are flawed and should not dictate the classroom or be a metric of one’s intelligence.

The Problem With AP & IB Exams

The AP and IB programs were created with the purpose of equipping high school students with the necessary skills and preparation to build a better future. “Thinkers, Communicators, and Risk-Takers” are among the many learner qualities that the IB program strives to instill within its students. However, the purpose of these values crumbles as participating in these rigorous and content-heavy classes confines students to overhauling and memorizing a year’s worth of content in just a few weeks. They miss the opportunity to gain these important life skills in the hassle of cramming content they won’t be able to retain after the exam.

“Much of the material learned over the class is forgotten shortly after the test, so we should focus on ways of learning that really immerse the student in their studies, as that is more applicable to the real world,” an anonymous student said.

Back-to-back tests, intense workloads, and unhealthy levels of stress are what AP & IB curriculums entail to put students’ college readiness to the test. However, these structures are not an indication or replication of college life. Although college classes may cover the same content, classes occur less often and are more project-based, giving students more time and freedom to learn. If these programs truly wish to prepare the students for their futures in college, then they must be an accurate representation of the university and not burn their students out in the process with a heavy workload.

At the end of the day, a year of intense workload simply comes down to one test. No matter the effort one puts in or the grades one receives throughout the year, students have one chance to prove to College Board or the IB Organization if they should receive college credit. The principle behind this remains arbitrary and unfair. A student’s performance could have faltered on the day of their exam, or they just might not be the best at taking such exams. However, to take away their chance of receiving the college credits after they endured the difficulty of the class, and even succeeded in it, is unfair.

“I think it’s better to measure you on how well you’ve performed over the course of the class,” an anonymous student said. “The tests favor students who are just better test takers, faster readers, and who have greater access to study materials and better teachers.”

Out of the ten months in a school year, teachers have to allot almost an entire month to simply review content and the structure of the exams. That is one whole month gone towards preparing for the exam — one month that could’ve gone diving deeper into content, doing projects, and learning more about the subject. Students’ free learning is not only being restricted by these exams but also teachers’ freedom to teach beyond what is written in the curriculum. These exams that last just a few hours dictate the whole trajectory of the school year and hinder free learning.

“I think [with] the time we have and the amount of information we have to learn, it is very difficult to teach beyond the material,” a student said. “I would love to learn the content above and beyond the test since teachers who do that tend to have engaging classes and higher scores in the AP [and] IB tests.”

A Look To Alternatives

In order to combat the poor retention and intense stress from AP and IB classes, College Board and the IB Organization must take inspiration in what they’re attempting to prepare students for: college classes. By replicating the framework of college classes, high schools foster an environment where students can learn freely and truly understand what is needed in college.

Discussion-styled learning, a major component of college classes, is the first implementation that these programs should consider as it will counter the tendency to memorize and cram content. Students lead the discussion circles and offer their different perspectives rather than just being fed lesson plans and slideshows that cover concrete ideas. This not only is a more accurate method of preparing students for college but also a way to increase student motivation. These discussions and seminars replacing the abundance of notes and homework assignments can be just as effective in preparing students for their exams while also allowing students to develop the critical values that programs like IB advocate for.

While IB already heavily focuses on projects, AP must also integrate more project-based learning into its grading system. This will be giving students an opportunity to apply their knowledge outside the bounds of the AP exam and will enable them to practice free learning. These large projects should factor into whether students should receive college credit for the class because if they can apply concepts to the real world, they should be recognized for their mastery of the subject.

Lastly, there needs to be a more holistic approach to determining whether students should receive college credit or not- the entire outcome of a class cannot ride on a single exam. Instead, these projects and assignments throughout the year should weigh into whether one receives college credit or not.

The AP and IB programs are essential components in building better futures for high school students, but there needs to be a change in their structure and exams to ensure that students are actively learning and preparing for college and beyond.