High school junior Darryl George was in tears when he was informed that he would be suspended for violating his school’s dress code. In September of 2023, there was a national uproar when George was suspended three times from Barbers Hill High School in Mont Belvieu, Texas. As of January, he hasn’t been in school since Aug. 31, all for wearing his hair in twisted locs. George was suspended the same week Texas signed Dove’s Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair (CROWN) Act, a bill that prevents discrimination based on hair, into law. George’s school said that his hairstyle was in violation of their dress code, which prohibits male students from having hair that extends past their eyebrows.

George’s family said that all the men in his family wear dreadlocks as a connection to their culture and heritage and that George has been growing dreadlocks for 10 years, but there was never any issue until he was suspended from school. George’s family filed a lawsuit against Governor Greg Abbott, Attorney General Ken Paxton, and the school district where George is enrolled, for failure to enforce the CROWN Act. The trial date has been set for Thursday, Feb. 22.

This trial perfectly represents the reality of one of the lesser-known forms of anti-Black racism that Black Americans are all too familiar with, hair discrimination. Hair discrimination is defined as negative stereotypes towards natural Black hairstyles and textured hair. Hair discrimination goes back hundreds of years and unfairly impacts Black Americans, primarily women, in every facet of their lives.

Anti-Black prejudice towards hair that caused George’s suspension is nothing new, of course. Like all of America’s anti-Blackness, its origins trace back to slavery. Enslaved field workers often covered their hair with scarves, due to the harsh conditions of their work, slaves who worked inside the “big house” often mimicked the hairstyles of their owners, either with wigs or shaping their own hair to match. But when free Creole (French and Black) women in New Orleans began to style their curls in elaborate styles, the city passed the Tignon Laws, requiring these women to cover their hair with a scarf, whether they were enslaved or not, to signify that they were part of the enslaved class.

But during the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s and ’70s, wearing natural hair became a popular form of protest against bigotry and white-centric beauty standards. Activists such as Angela Davis wore an afro as a staple of rebellion, and Marcus Garvey encouraged Black women to wear their hair naturally. While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law, prohibiting racial discrimination in the workplace, it did not account for equal treatment of Black culture at work.

A study from Dove’s CROWN research found that Black women’s hair is two and a half times more likely to be perceived as unprofessional, Black women are 54% more likely to feel like they have to straighten their hair for job interviews and 41% actually did so. In addition, Black women with coily or textured hair are two times as likely to experience microaggressions in the workplace than Black women with straighter hair.

Hair discrimination isn’t only prevalent in the workplace, as it commonly affects children in schools. Examples of Black students being unfairly discriminated against in school can be seen clearly in every corner of the country. In 2017, two Black sisters, Mya and Deanna Cook, were banned from their extracurricular activities and prom, as well as threatened with suspension from Mystic Valley Charter School in Boston, all for refusing to remove their braided hair extensions. The school banned hair extensions in the dress code and told the Cook sisters that their hair was deemed distracting. Incidents of natural hair being penalized are common throughout the years and across the country, from elementary schools in Louisiana, where a girl was humiliated in front of her class when she was sent home for her braided hairstyle, to a high school wrestler in New Jersey, who was forced to cut his dreadlocks or forfeit a match.

This inexcusable discrimination against Black hair puts Black people in a tricky paradox between wanting to be proud of their heritage and culture which those before them fought for them to display, but also being faced with the temptation to straighten their hair to increase their chances of success. It is absolutely archaic to force someone to choose between their culture and their livelihood.

After all the bigotry, prejudice, and microaggressions they endure, Black people, especially women, are just trying to live their lives, but they are subjected to the worst hypocrisy of all: watching white people wear their culturally significant hairstyles and sometimes even being praised for doing so.

Even in recent years, white celebrities have routinely put on Black hairstyles for fun, such as Adele in Bantu knots, Miley Cyrus in dreadlocks, and Kim Kardashian repeatedly wearing box braids. This has even led box braids, a traditional African hairstyle that’s been around for hundreds of years, to be nicknamed “Kim K braids.”

Actress Bo Derek famously wore Fulani braids, a traditional hairstyle from the Fulani tribe of East and West Africa, in the 1979 movie 10. Though Fulani braids are a hairstyle with deep and rich ties to African culture, Derek was credited with popularizing the braids, and the braids were then nicknamed “Bo Derek Braids,” stripping them of their cultural identity.

This harmful effect was most clearly seen in the Rogers v. American Airlines case of 1981, when Renee Rogers, a Black flight attendant who had been working for American Airlines for 11 years, was told by her superiors that her cornrows were in violation of their grooming policy. Rogers sued the airline for race discrimination, claiming that the policy violated her rights under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In court, The Southern District of New York Court sided with American Airlines, claiming that cornrows were a feature that could simply be changed. Since Derek, a white woman, had recently popularized cornrows in 10, the court deemed the style a trend, meaning the American Airlines policy didn’t affect only Black women, so therefore it was not discriminatory.

More recently, these displays of uneducation about the history, culture, nuance, and significance of hair in Black American culture caused uproars on social media, with people claiming white celebrities who wore traditionally Black hairstyles were guilty of cultural appropriation.

Common opponents of the cultural appropriation argument claim that there is no reason to be upset about white people wearing Black hairstyles, saying, “it’s just hair.” But it is never “just hair.”

The effect of white people appropriating Black hairstyles does not exist in a vacuum, but rather it negatively and directly affects Black people, as it can lead people not seeing Black hairstyles as belonging to Black people. And when Black people, especially Black women, try to participate in the culture that is rightfully theirs, it is seen as hopping onto a popular trend.

To respond to the criticism of cultural appropriation with “it’s just hair” is insulting to the culture, heritage, and history of Black women’s hair. It is insulting to what Black people go through when they face constant struggles in every facet of their lives for something as simple as their hairstyles. It is a slap in the face to every Black person who was told their hair was “unprofessional,” “nappy,” “unruly,” or “ghetto,” while white people get to be called “edgy,” “trendy,” and “stylish.” When Cyrus wore dreadlocks to the 2015 VMA’s, fashion TV show Fashion Police tweeted that Cyrus was the “best dressed,” while Fashion Police host Giuliana Rancic and E! red carpet co-host Kelly Osbourne commented on Zendaya’s dreadlocks at the 2015 Oscars, with Rancic saying she felt they “smelled of patchouli,” with Osbourne adding “or weed.”

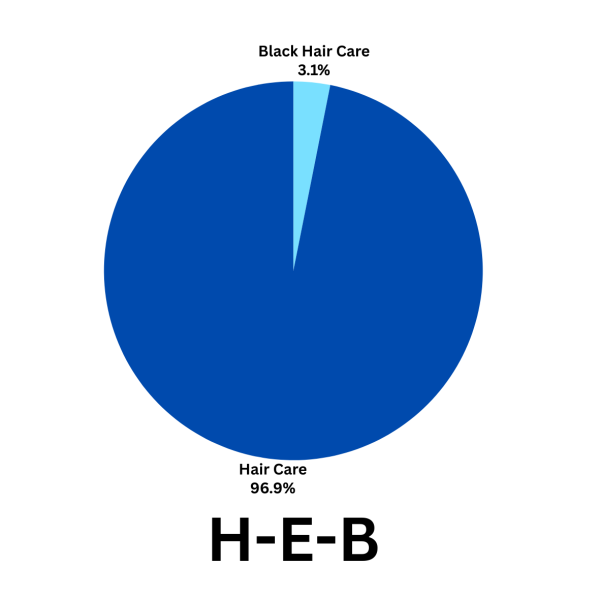

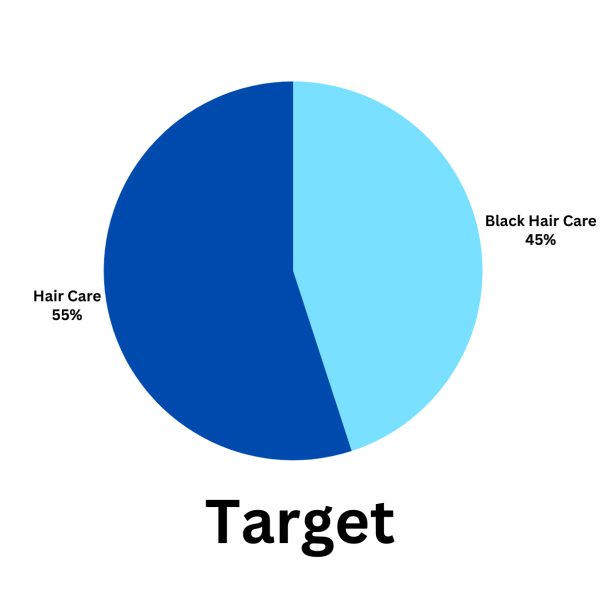

Without all the bias and discrimination that comes with Black hair, multiple Black people experience trouble finding hair stylists that can do their hair, especially for those who live in rural, or mostly white areas. It’s also tough for Black people to access Black hair products in grocery stores. Many large grocery store chains have made a push to include more options for textured hair after many came under fire for locking up Black hair care products in lockboxes only the employees could open with a key. However, out of all the shampoo, conditioner, and styling products offered on Target and H-E-B’s websites, only 45% of hair care products offered on Target’s website were for textured hair, and only 3% of hair care products on HEB’s website were for textured hair.

In addition to Black hair care products being hard to find, they are often more expensive once you are able to. One 13-ounce bottle of SheaMoisture Raw Shea Butter Deep Moisturizing Shampoo costs $11.41 at H-E-B, and $10.99 at Target, compared to a 17.9-ounce bottle of Pantene Pro-V Classic Clean Shampoo, which is $6.29 at Target, and $6.21 at H-E-B. This makes SheaMoisture, on average, 0.51 cents more expensive per ounce than Pantene, despite having 4.9 fewer ounces.

The constant lack of accessible and affordable hair products puts Black people at a systemic disadvantage when caring for something as basic and necessary as their personal hygiene. When products are hard to find and expensive, and when salons do not have employees who are skilled in natural hair care, Black Americans hit a dead end, leaving them no other option but to straighten their hair. Grocery store chains need to carry a wider variety of products, and a wider variety of Black hair care products, as Black hair texture is a spectrum, from curly, to coily, to kinky. The lack of variety in Black hair care products can lead to Black people not only struggling to find Black hair care but also struggling to find Black hair care that can be used on their specific hair type.

So far, the CROWN Act has been signed into law in 23 states, and legislation is in the works in 21. However, it is absolutely crucial that the CROWN Act is signed into law on a federal level. It is abhorrent that hair discrimination has been allowed to persist, and only when the CROWN Act is made a federal law will true equality be achieved.

Mary Hobbs • Mar 5, 2024 at 12:18 pm

Bravo. What a well written article that is backed with rich history and curent facts. My own personal story, for years, I only wore my natural hair in two styles- straightened and two strand twist. There wasn’t a policy or rule but I subconsciously didn’t want coworkers commenting on my hair all the time! (How it changed weekly, how the length was different, if it was mine!) It took many years in the profession field to be okay with rocking a wash n go. Now this is my signature style and I’m okay with changing up my hair just like I do my clothes!