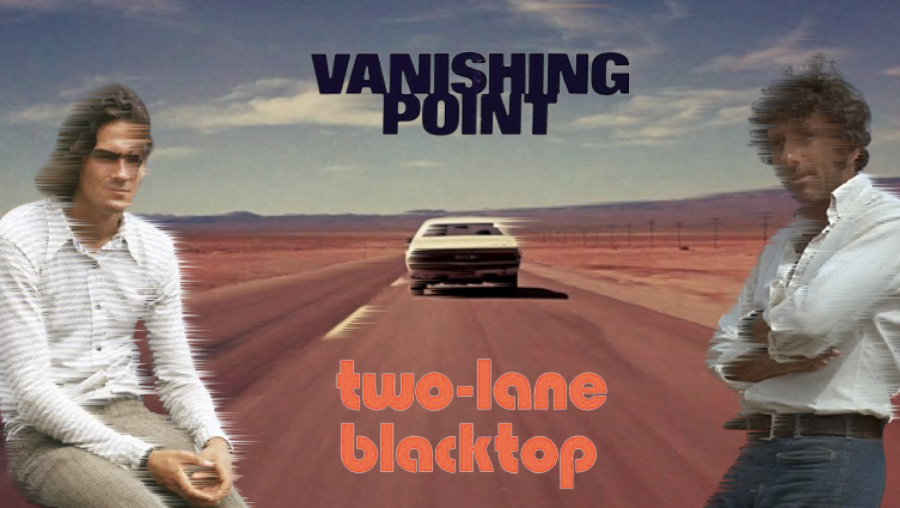

‘Two-Lane Blacktop’ vs ‘Vanishing Point’: 1971’s Weirdest Road Movies

1971 saw the release of two very different but also very similar road movies. Here’s why they’re worth watching.

In the first half of 1971, two oddly similar movies were released. While their filmmaking styles were wildly different and they were produced independently from one another, the two films both showcased existentialism on the American road, a seemingly endless race cross-country, a downbeat ending, and gay hitchhikers. These two films are little-seen today, which is unjust. As these films celebrate their 50th anniversaries this year, let’s examine what makes them special, and why they shouldn’t be forgotten.

Both movies began production in the late ‘60s, and used real life events for inspiration. Blacktop’s genesis began in 1968 when screenwriter Will Corry took a cross-country road trip across America. Corry’s script, featuring two gear heads who travel across America while being tailed by a young woman, found its way into the hands of Monte Hellman, a brainy director who was toiling in the exploitation world of Roger Corman. Hellman, like his contemporaries Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese, was a smart and talented filmmaker who currently worked with the cheap and thrifty producer Corman on his low budget schlock films. Unlike his peers, Hellman hadn’t had a hit like Easy Rider or The Godfather, so when he received Corry’s script he decided to direct it despite misgivings about the material itself. He hired Rudy Wurlitzer to rewrite the script, as well as fellow underrated ‘70s director Floyd Mutrux to offer input on the cars.

Wurlitzer created the all-important fourth character in the story, the chattery and friendly GTO, played by Warren Oates. GTO, like all of the film’s characters, is identified not by his name, but by a single word, which in this case, is the name of his car. In the final film, GTO challenges the two younger men (The Driver and The Mechanic) and their lady friend (The Girl) to a race, from their current location in California (actually New Mexico, disguised as the Sunshine State) to Washington DC. Their relationship is strange. The duo don’t seem to dislike GTO, but they don’t like him either. In fact, they seem to have no opinion of him either way. Although GTO seems to harbor a grudge towards the two, somewhere in the middle is The Girl. She kisses GTO, is intimate with The Mechanic, and flirts with The Driver. In the end, however, she leaves them behind. Their relationships are strange, and made even stranger by the stark contrast between the characters. In contrast to the duo’s monotone voices and normcore fashion, GTO is loud, talkative, and dressed in constantly changing garish sweaters. Along the way, he picks up various hitchhikers, who supply some much-needed comic relief. One of them even espouses the film’s theme. In a short vignette, a hippie enters the car and decries his life as pointless and meaningless. He then asks to be let out of the car. The movie as a whole seems to suggest that the characters’ journey is ultimately meaningless, and this is an idea it shares with Vanishing Point.

Vanishing Point was based on two separate news stories, one about a disgraced police officer and the other about a high-speed chase that ended in disaster when the car hit a roadblock. These two concepts were mixed into a satisfying whole by G. Cabrera Infante, a Cuban writer who had a one-time association with Fidel Castro. It eventually reached the desk of Richard Sarafian, Robert Altman’s brother-in-law, who was interested in the counter-cultural themes of the script. The story centers around Kowalski, a stone-faced ex-cop who is told to deliver a car from Denver to San Francisco. He takes some drugs and becomes determined to break every possible rule, stopping only when he needs gas and a bathroom. Aiding him on his journey is the psychic DJ Super Soul, who tells him where the police are and gives the movie its strange gospel-rock soundtrack. Along the way, Kowalski encounters several crazy characters, including an elderly snake catcher, the aforementioned gay hitchhikers, and a nude motorcycle rider. The driving scenes are tightly edited, fast-paced, and scored with driving rock music. This is in stark contrast to the driving scenes in Blacktop, which feature no music, have long, unbroken shots, and feature decidedly non-crazy characters, barring the occasional wacky hitchhiker that GTO picks up.

On the surface level, Vanishing Point is a better movie because for one, it’s more exciting. But upon watching the two films, you’ll find Two-Lane Blacktop a much more interesting film. Both of them experiment with having mysterious lead characters, but Blacktop succeeds better in this front. Vanishing Point’s Kowalski is given some token backstory about being a former cop, but The Driver and The Mechanic’s lives before the film begins are left up to our imagination. GTO changes his backstory every time a new hitchhiker shows up, but at one point he seems to almost reveal his backstory to the Driver, beginning a spiel about his wife and kids. The Driver quickly shuts him up, leaving his true past a mystery.

Barry Newman plays Kowalski as a hard-edged road warrior, but despite the backstory, we don’t care much about him. Sarafian’s original choice was Gene Hackman, an actor who would have excelled in the part. While Newman does a fine job with the material he’s given, he’s ultimately not as interesting as the leads of Blacktop. This is ironic considering the extreme mundanity of the two heroes at the center of Hellman’s movie, played with a monotone flavor by pop stars James Taylor and Dennis Wilson. Wilson, the hunky drummer from The Beach Boys, was connected to Charles Manson and was known for his love of cars, so his casting as The Mechanic made some sense. Taylor, on the other hand, was an earnest folk singer-songwriter whose style of music was so soft and pleasant that his nickname was “Sweet Baby James.”

At first glance, he doesn’t seem to fit. But he actually gives an intriguing performance. Both Wilson and Taylor never acted again, save for cameos as themselves, and it’s easy to see why. Their acting styles are so downbeat and un-theatrical that it’s hard to believe they’re actually acting. Their characters are about as far from a normal movie character as you can get, devoid of cliches and characterization. With their long hair and car obsession, one would assume them to be hippies, but they never engage in drugs or any other activity, really, other than driving. While this sounds like a terrible concept on paper, they fit the movie well. Taylor has an intensity that fits the character well, although he never changes his expression throughout the whole movie. Wilson has charm, but of the four leads, he is the least interesting. It was Laurie Bird as The Girl that really captured my attention.

The Girl is the closest the movie gets to a well-defined, realistic character. She has a backstory, a character arc, and a charming personality that feels very realistic. Towards the end of the movie, she spontaneously leaves The Driver and The Mechanic to drive off with a young motorcyclist, seemingly on a whim. She knows she has to get out because if she doesn’t, she’ll be stuck on the road for eternity. And for all we know, the race could go on forever, because of the movie’s notorious ending.

In Vanishing Point, Kowalski reaches a roadblock set up in a small town. We saw him evade the blockade earlier in the film in a scene that we can assume was a flash-forward to a time later in the movie. But this time, Kowalski doesn’t turn back. He keeps driving. And he smashes into the roadblock, causing his car to blow up in a glorious explosion. It’s an ending that echoes the similarly downbeat denouement of Easy Rider. Kowalski has been speeding through his life with such force that it will take an immovable object to stop him. He has reached the vanishing point of his life. Earlier in the film, we see Kowalski speak to a black robe-clad woman who foretells of his coming doom. It’s during this conversation that we finally see Kowalski relax. The next morning, Super Soul tries to warn him about the roadblock. He doesn’t listen. The music switches to a religious song about Jesus. Kowalski is putting his faith in a higher power now, but the higher power he should have been listening to was Super Soul. As he is about to hit the roadblock, he smiles. Does he want to die? Or does he think he can survive? We’re not sure because what we see next is a large explosion.

Two-Lane Blacktop also ends in fire, but it’s a different kind. This fire breaks not only the fourth wall, but also the movie itself. The Driver has stopped for another side-race, to be held concurrently while his race against GTO occurs. It’s a race within a race, a pointless endeavor that won’t yield anything. As The Driver sets out, the audio drops out and the footage slows down. Then, we see the film begin to burn and warp, like it would in a faulty print. Seeing this in the movie theatre you might think the projectionist messed up. Then the credits roll.

Needless to say, both have rather abrupt endings. But both also seem to have different views of their characters. Vanishing Point portrays Kowalski as a martyr of sorts, a speed freak whose final sacrifice only happened because he couldn’t slow down. It’s a satisfying ending, made even better by Newman’s cocky smirk right before he explodes. The ending of Blacktop, on the other hand, doesn’t give us anything. We don’t know what happened to The Driver, or any of the other characters. There’s no prior fourth wall breaks and we can only wonder what happened afterwards. But in a way, it doesn’t matter. The race will keep going. The characters will continue racing, stopping, and picking up hitchhikers. It won’t matter who wins the race because there’s so little actual competition and the stakes are dubious at best. We wonder as viewers: will we be satisfied or happy if we know who won? I somehow doubt it because the film hasn’t framed the race like it’s a chase, with an underdog and a villain or big shot.

Vanishing Point doesn’t portray it like that either. The reasons for Kowalski’s trip are forgotten about, and by the end, he’s just driving to get his speed fix. The people chasing Kowalski are faceless police officers, and perhaps Kowalski would have been one of them if he hadn’t given up his job as a cop.

Besides the release year and subject matter, the two films also share a plot point: the introduction of gay hitchhikers into the storyline for exactly one scene. As is to be expected for two movies released in 1971, these portrayals are far from perfect. Vanishing Point’s scene would be considered more offensive now, as the duo of hitchhikers perform a stick-up against Kowalski. In Two-Lane Blacktop, the scene is shorter and less offensive. Iconic character actor Harry Dean Stanton plays the hitchhiker here, and he makes a pass at GTO, which he quickly spurns. Neither scene contributes to the plot whatsoever but it’s interesting to note their presence nevertheless.

Ultimately both films have the same message, but they present it in different ways. Both represent the futility of the American road, a highway with no end, and filled with malaise. The concept of an endless road was a popular concept in the ‘70s, as can be seen with the popularity of Smokey and the Bandit and other trucking films. The death of the ‘60s revolution movement and the seemingly endless Vietnam war left Americans feeling as if the decade would truly never end, only going on until the film burned up, much as it does at the end of Two-Lane Blacktop. Both films suggest that the only end will be achieved with total oblivion. Of course, the world didn’t end and the national malaise would soon be lifted as the country defied into the upbeat ‘80s. But the message and vibe of these two films, that of weariness, boredom, and uncertainty, still resonates today.

Two-Lane Blacktop and Vanishing Point are both frustratingly hard to find. Free copies can be found on corners of the internet, but both are available on Blu Ray and DVD, with Two-Lane Blacktop in particular being packaged in a luxurious, original script-including edition. Both seem dangerously close to falling into total obscurity. So don’t let it happen. Watch these films and spread the word.

Class of 2023

I am currently Westwood Horizon's video editor, and also one of the hosts of Friendcast, our website's podcast video series. In addition...